Double Decker Enrichment cages have no effect on long term nociception in neuropathic rats but increase exploration while decreasing anxiety-like behaviors

by Pascal Vachon

Correspondence: Pascal Vachon

Correspondence: Pascal Vachon

University of Montreal, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of

Veterinary Biomedicine,

Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec, Canada J2S 2M2

Tel + 1 (450) 773-8521 ext. 8294

E-mail pascal.vachon@umontreal.ca

Summary

In this present study, we investigated the impact of environmental enrichment in Sprague Dawley rats up to three months after a chronic or sham nerve injury. Sprague Dawley rats were housed in either standard polycarbonate cages or rat enrichment cages. Following 2 weeks of training and the recording of baseline behavioral values, half of the animals underwent a right sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury (CCI) surgery under general anaesthesia to induce chronic neuropathic pain. The other animals underwent a sham surgery. Animals were then evaluated once a month for 3 consecutive months in different behavioural tests for of mechanical and heat sensitivities as well as for exploration and anxiety-like behaviors. Mechanical and heat sensitivities were also tested at 15 days following the surgery. One month following the surgery, half of the rats in each group (CCI and sham) were either left in the standard rat cages or placed in the Double Decker cages. Environmental enrichment did not affect the mechanical or heat sensitivity of neuropathic animals; however exploration increased, and anxiety-like behaviours decreased, significantly (p<0.01). These results clearly show that environmental enrichment can have a significant impact on exploratory and anxiety-like behaviour in neuropathic rats without modifying pain hypersensitivity.

Introduction

Enrichment of both social and physical life is gaining interest for

the treatment of chronic pain, since an enriched environment may be

protective against the development of chronic pain. For example,

studies in animals (Tagerian et al., 2013; Vachon et al., 2013; Gabriel et al., 2009,

2010a, 2010b; Tall 2009) and humans (Smith et al., 2003; Ulrich, 1984) looking at

the effects of the environment on pain recovery following surgery

showed a significant alleviating effect with environmental enrichment.

Environmental enrichment may also protect against the development of

depression and anxiety disorders, both of which are commonly

associated with chronic pain in animals (Tagerian et al., 2013; Seminowicz et al., 2009; Suzuki et al.,

2007) and humans (Campbell et al., 2003; Daniel et al., 2008; Dick et al., 2008;

Haythornthwaite et al., 2000; Kewman et al., 1991; Petrak et al.,

2003). Social isolation on the other hand has unclear effects on pain

sensitivity. Adler et al. (1975) and DeFeudis

et al. (1976) reported that isolation had no effect on pain

behaviors; however Panksepp (1980) suggested that it may increase pain

sensitivity.

Rodents living in enriched environments show less pain behavior

following a peripheral nerve or central nervous system injury than

those living in standard or restricted environments (Tall, 2009; Gabriel et al., 2009; 2010a; 2010b, Berrocal et al.,

2007; Lankhorst et al., 2001). However in these studies animals were kept in the enriched

environment from the time of injury onward. Most studies have been

conducted with healthy non-injured animals (Chourbadji et al., 2008; Rossi & Neubert, 2008; Smith et al.,

2003, 2004 & 2005) as well as animals with inflammatory (Gabriel et al., 2009; 2010a,b; Tall, 2009) and neuropathic pain (Stagg et al., 2011). It has recently

been shown that pain can be alleviated by environmental enrichment

well after the establishment of chronic pain in mice (Vachon et al., 2013; Tajerian et al., 2013). In this study, we investigated whether leaving neuropathic rats in

standard polycarbonate cages or putting neuropathic rats into

enrichment cages one month after surgery would alter pain sensation as

well as associated anxiety-like and exploratory behaviors.

Materials and methods

Animals and husbandry

Twenty-four Sprague Dawley rats (CRL:CD[SD]; Charles River,

St-Constant, Canada) weighing between 225-250 g were purchased for

this study. Following their arrival, they were kept in a standard

laboratory animal environment (fresh filtered air, 15 changes/ hour;

temperature, 21 ± 2oC; humidity 50 ± 20%; and light-dark cycle, 12:12h). Rats were housed on hardwood bedding (Beta

chip, Northeastern Products, USA) with only black PVC tubing for

environmental enrichment and they were placed 2 per cage in large

polycarbonate cages (48x38x21 cm; Tecniplast) up to one month

following surgery. Rats received tap water and a standard laboratory

rodent diet (Charles River Rodent Chow 5075, Canada)

ad libitum. The Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experimental protocol prior

to animal use in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian

Council on Animal Care (1993).

Following their arrival and a one-week acclimation period, rats were

trained for two weeks to the different behavioral tests and baseline

values were taken. A peripheral mononeuropathy was then produced in 12

animals using the chronic sciatic nerve constriction (CCI) model (Bennett and Xie,

1988). Briefly, following anesthesia with isoflurane

(AErrane; Baxter), the right common sciatic nerve was exposed via

blunt dissection at the level of the thigh (biceps femoris).

Four loose ligatures were placed around the right sciatic nerve with

4.0 Catgut suture material. The overlying muscles were then sutured

with 3.0-vicryl and the skin was closed with a 2.0 silk suture.

Animals were then tested in all behavioral tests once a month for 3

consecutive months following the surgery. In addition, mechanical (von

Frey test) and heat sensitivity (Hargreaves test) were also evaluated

15 days following the surgery. The other 12 animals underwent a sham

surgery (same procedures without the sciatic ligatures).

One month following surgery (and behavioral evaluations at one month),

CCI rats were randomly assigned to either of 2 groups: 1) nerve injury

and environmental enrichment (NE, n=6) or 2) nerve injury and standard

housing (NS, n=6), while sham animals were assigned to either 1) sham

surgery in environmental enrichment (SE, n=6) or 2) sham surgery and

standard housing (SS, n=6). Environmental enrichment consisted of

Double Decker enrichment cages (Tecniplast Inc.) and for the standard

housing animals were left in the large polycarbonate cages.

Behavioral evaluations

For all behavioral tests, each apparatus was washed with a very

diluted cleaning solution between two consecutive animals to minimize

odor interference.

Mechanical sensitivity Calibrated von Frey filaments

(Stoelting Co.) were applied for 4 sec or until withdrawal. The

stimulus force ranged from 1 - 26 g, corresponding to filament sizes

4.08 – 5.46 g. For each animal, the actual filaments used within the

aforementioned series were determined based on the lowest filament to

evoke a positive response using the up-down method. Animals were

acclimated to the experimental setup for 15 minutes prior to testing.

The mechanical sensitivity was assessed on the plantar surface of both

hind paws.

Hargreaves thermal sensitivity test: Thermal sensitivity was

evaluated using a Hargreaves apparatus (IITC Life Science) as

previously described (Hargreaves et al., 1988). Each animal

was placed in a Plexiglas chamber with the ground floor made of heated

glass (29-31°C). Animals were allowed to acclimate to the experimental

set up for 15 min prior to testing. Then radiant heat generated by a

high intensity light bulb (40W) was directed to the plantar surface of

a hind paw. The lamp generated noxious a heat stimulus. The time the

animal took to lift its paw from the floor was recorded and noted as

the thermal threshold. Rats were tested in groups of 4 animals. The

test began alternatively with the right or the left hind paw to

prevent any anticipatory behavior. A cut-off time for the radiant

stimulation was set at 20 sec to minimize tissue injury.

Open field test: Spontaneous exploratory

behavior was evaluated in a transparent open field apparatus (60 x 60

cm), placed in a quiet room. The floor of the apparatus was divided

equally into nine squares (20 x 20 cm2). Rats were individually placed

into the open field on the central square, and their spontaneous

behavior was videotaped for 5 minutes before being scored by an

observer blinded to the experimental protocol. Subsequent analysis of

the total number of squares visited, as well as the number of times

rats stood on their hind paws, was used to assess general motor

activity and exploration.

Elevated plus maze: An elevated plus maze

apparatus was placed in a quiet room. The apparatus consisted of two

open arms (100 cm long x 10 cm wide) across from each other and

perpendicular to two closed arms (2 x 45 cm long x 10 cm wide x 30 cm

high). The entire apparatus was positioned 60 cm above the floor. Rats

were individually placed at the intersection of the four arms, head

towards an open arm. Their spontaneous behavior was videotaped for 5

minutes before being scored by a blinded observer. The total time

where partial (at least two front paws in contact with the open arm)

or total body was on an open arm was measured.

Statistical analysis

A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed for all behavioral

tests. Post hoc Tukey tests were performed to assess the

difference between groups at different time points. The level of

significance was set at 0.05. Data are presented as mean

± SD .

Results

The von Frey filaments and Hargreaves results are presented in s 1

& 2. Results from non-enriched, as well as enriched, environments

were pooled together since no significant differences occurred with

environmental conditions. Only the ipsilateral hind paw of

nerve-injured animals was hypersensitive to mechanical stimuli up to

60 days following the surgery (p<0.05 at 15 days and p<0.01 at

30 & 60 days). The same general findings were obtained for the

Hargreaves test (p<0.01 at 15, 30 & 60 days for the ipsilateral

hind paw in CCI animals). At 90 days following the surgery, CCI

animals were no longer neuropathic for either mechanical or heat

sensitivities.

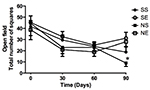

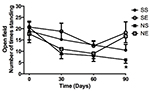

When looking at the total number of squares entered in the open field

test (Figure 3) and the number of times the animals stood on their

hind paws (Figure 4) over a 5 minute period, there were no differences

between the experimental groups up to 60 days, however a decrease in

exploration occurred over time, which could be associated with

learning. At 90 days a clear difference in both behaviors occurred for

the neuropathic animals: enrichment cages had a clear benefit over the

standard environment (p<0.01). Although not significant, a trend to

increased exploration and standing behavior at 90 days occurred for

sham animals placed in enrichment cages.

With the elevated plus maze (Figure 5) all groups explored the open

arm for the same percentage of time up the 30 days post-surgery. At 60

days, sham animals in enriched environment were clearly less anxious

than the sham animals in the standard environment (p<0.01), with no

significant difference seen amongst other groups. At 90 days

post-surgery, neuropathic animals in the enriched environment clearly

showed less anxiety-like behavior (greater exploration of the open

arm) than neuropathic animals in the standard environment (p<0.01).

Discussion

Our results clearly show that environmental enrichment has a

significant impact on exploratory and anxiety-like behaviors, but

doesn’t affect pain hypersensitivity in a rat model of

neuropathic pain. At 60 days post-surgery, environmental enrichment

did not affect pain threshold to mechanical and heat stimuli in rats,

an effect that was clearly seen in mice (Vachon et al, 2013).

At 90 days post-surgery, the loss of heat and mechanical pain

sensitivities in neuropathic animals is a normal finding when using

the CCI model (Coggeshal et al, 1993). Interestingly these

animals benefited the most from the enrichment cages (decreased

anxiety and increased exploration) even though they were no longer

neuropathic. Since standing and exploratory behaviors increased, and

anxiety-like behaviour decreased, in neuropathic animals when housed

in the Double Decker cages, this strongly suggests that their

well-being increased. Importantly, cage size would appear to influence

some higher brain functions without affecting chronic pain processing.

We have previously shown (Vachon et al., 2013; Tajerian et al., 2013) that environmental enrichment in mice had an alleviating effect on

well established chronic neuropathic pain and anxiety-like behaviors.

One of the main components of the enriched environment in this

previous study was a running wheel, and exercise is known to decrease

pain symptoms and improve motor function in chronic pain models. Stagg

et al. (2011), demonstrated that thermal hyperalgesia in a

rat model of neuropathic pain is reversed with exercise.

Interestingly, reversal of sensory hypersensitivity was seen even when

exercise was initiated 4 weeks after spinal nerve ligation, and

returned 5 days after discontinuing exercise. In the present study,

the main focus was the effect of cage size on pain-related behaviors

and therefore the addition of exercise toys could very well provide an

additional benefit, if the objective is to treat pain. Exercise

appears sufficient to have a significant alleviating effect on

neuropathic pain symptoms, and clinical studies in humans suggest that

exercise decreases pain symptoms in chronic pain patients (Malmros et al., 1988; Ferrel et al., 1997; Gowan et al., 2004;

Hayden et al., 2005; Robb et al., 2006; Chatzitheodorou et al.,

2007).

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that environmental

enrichment cages appear to be a very interesting option when studying

neuropathic pain in a rat model, since pain behaviors didn’t

appear to be affected but there was evidence for increased animal

welfare.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the financial support of the Laboratory Animal Research Fund (Dr Pascal Vachon research lab), the donation of Double Decker cages from Tecniplast, the technical and material support (Tecniplast standard rat cages) of Ste-Justine Hospital Research Centre, and Dr Geneviève Roy who did all video data acquisition.

References

-

Adler MW, C Mauron, R Samanin &, L Valzelli: Morphine

analgesia in grouped and isolated rats. Psychopharmacologia 1975,

41, 11-14.

-

Bennett GJ & YK Xie: A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat

produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain

1988, 33, 87-107.

-

Berrocal Y, DD Pearse, A Singh, CM Andrade, JS McBroom, R Pentes

& MJ Eaton: 2007. Social and environmental enrichment

improves sensory and motor recovery after severe contusive spinal

cord injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 1761-1772.

-

Campbell LC, DJ Clauw & FJ Keefe: Persistent pain and

depression, a biopsychosocial perspective. Biol. Psychiatry 2003,

54, 399-409.

-

Canadian Council on Animal Care: Guide to the Care and Use

of Experimental Animals. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 1993.

-

Chatzitheodorou D, C Kabitsis, P Malliou & V Mougios: A

pilot study of the effects of high intensity aerobic exercise versus

passive interventions onpain, disability, psychological strain, and

serum cortisol concentrations in people with chronic low back pain.

Phys. Ther. 2007, 87, 304-312.

-

Chourbaji S, C Brandwein, MA Vogt, C Dormann, R Hellweg & P

Gass : Nature vs nuture, can enrichement rescue the behavioral phenotype

of BDNF heterozygous mice ? Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 192, 254-258.

-

Coggeshall RE, PM Dougherty, CM Pover & CM Carlton:. Is

large myelinated fiber loss associated with hyperalgesia in a model

of experimental peripheral neuropathy in the rats. Pain 1993, 52:

233-242

-

Daniel HC, J Narewska, M Serpell, B Hoggart, R Johnson & ASC

Rice:

Comparison of psychological and physical function in neuropathic

pain and nociceptive pain, implications for cognitive behavioral

pain management programs. Eur. J. Pain 2008, 12, 731-741.

-

DeFeudis FV, PA DeFeudis & E Somoza: Altered analgesic

responses to morphine in differentially housed mice.

Psychopharmacol. 1976, 49, 117-118.

-

Dick BD, MJ Verrier, KT Harker & S Rashiq: Disruption

of cognitive function in fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain 2008, 139,

610-616.

-

Ferrel BA, KR Josephson, AM Pollan, S Loy & BR Ferrell: A randomnized trial of walking versus physical methods for chronic

pain management. Aging 1997, 9, 99-105.

-

Gabriel AF, MAE Marcus, WNM Honig, N Helgers & EA

Joosten:

Environmental housing affects the duration of mechanical allodynia

and the spinal astroglial activation in a rat model of chronic

inflammatory pain. Brain Res. 2009, 1276, 83-90.

-

Gabriel AF, G Paoletti, D Della Seta, R Panelli, MAE Marcus, F

Farabollini, G Carli & EA Joosten:

Enriched environment and the recoevry from inflammatory pain, Social

versus physical aspects and their interaction. Behav. Brain Res.

2010a, 208, 90-95.

-

Gabriel AF, MAE Marcus, WNM Honig & EA Joosten:

Preoperative housing in an enriched environment significantly

reduces the duration of post-operative pain in a rat model of knee

inflammation. Neurosci. Lett. 2010b, 469, 219-223.

-

Gowan SE, A Dehueck, B Voss, A Silaj & SE Abbey:

Six-month and one-year follow-up of 23 weeks of aerobic exercise for

individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 51,

890-898.

-

Hargreaves K, R Dubner, F Brown, C Flores & J Joris: A

new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in

cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 1998, 32, 77−88.

-

Kewman DG, N Vaishampayan, D Zald & B Han: Cognitive

impairment in musculoskeletal pain patients. Int. J. Psychiatry Med.

1991, 21, 253-262.

-

Lankhorst AJ,MP ter Laak,TJ van Laar ,NL van Meeteren, JC de

Groot & LH Sharma: Effects of enriched housing on functional recovery after spinal

cord contusion injury in the adult rat. J. Neurotrauma 2001, 18,

203-215.

-

Malmros B, L Mortensen, MB Jensen & P Charles : Positive effecs of

physiotherapy on chronic pain and performance in osteoporosis.

Osteoporos. Int. 1998, 8, 215-221.

-

Panksepp J: Brief social isolation, pain responsitivity,

and morphine analgesia. Psychopharmacol. 1980, 72, 111-112.

-

Petrak F, J Hardt, B Kappis, R Nickel & EU Tiber :

Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with

persistent somatoform pain disorder. Eur. J. Pain 2003, 7,

463-471.

-

Robb KA, JE Williams, V Duvivier & DJ Newham DJ: A pain

management program for chronic cancer-treatment-related pain, A

preliminary study. J. Pain 2006, 7, 82-90.

-

Rossi HL & JK Neubert: Effects of environmental

enrichement on thermal sensitivity in an operant orofacial pain

assay. Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 187, 478-482.

-

Seminowicz DA, AL Laferriere, M Millecamps, JSC Yu, TJ Coderre

& MC Bushnell:. MRI structural brain changes associated with sensory and

emotional function in a rat model of long-term neuropathic pain.

NeuroImage 2009, 47, 1007-14.

-

Smith MA, PA Bryant & McClean: Social and environmental

enrichment enhances sensitivity to the effects of kappa

opioids , studies on antinociception, diuresis and conditioned

place preference. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 76, 93-101.

-

Smith MA, JM McClean & PA Bryant: Sensitivity to the

effects of a kappa opioid in rats with free access to exercise

wheels, differential effects acrsoos behavioral measures. Pharmacol.

Biochem. Behav. 2004, 77, 49-57.

-

Smith MA, KA Chislom, PA Bryant, JL Greene, JM McClean, WW Stoops

& DL Yancey: Social and environmental influences on opioid sensitivity in rats,

importance of an opioid’s relative efficacy at the

mu-receptor. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 181, 27-37.

-

Stagg NJ, HP Mata , MM Ibrahim, EJ Henriksen, F Porecca, TW

Vanderah & MT Philip: Regular exercise reverses sensory hypersensitivity in a rat

neuropathic pain model, role of endogenous opioids. Anesthesiology

2011, 114, 940-48.

-

Suzuki T, M Amata, G Sakaue, S Nishimura, T Inoue, M Shibata

& T Mahimo : Experimental neuropathy in mice is associated with delayed

changes related to anxiety and depression. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 104,

1570-1577.

-

Tajerian M, S Alvarado, M Millecamps, P Vachon, C Crosby, MC

Bushnell, M Szyf & LS Stone:

Peripheral nerve injury is associated with chronic, reversible

changes in global DNA methylation in the mouse prefrontal cortex.

Plos One 2013, 8 e55259.

-

Tall JM : Housing supplementation decreases the magnitude

of inflammation-induced nociception in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2009,

197, 230-33.

-

Ulrich RS: View through a window may influence recovery

from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420-421.

Vachon P, M Millecamps, LA Low, SJ Thompson, F Pailleux, F Beaudry, MC Bushnell & LS Stone: Alleviation of chronic neuropatnic pain by environmental enrichment in mice well after the establishment of chronic pain. Behav. Brain Funct. 2013, 9,22.