Original scientific article

Housing behaviour of the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) under

laboratory conditions

by Royford Mwobobia1,2; Klas Abelson1; Titus Kanui2

1Department of Experimental Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical

Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Blegdamvej 3B, 2200 Copenhagen,

Denmark

2School of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, South Eastern Kenya

University

P O Box 170-90200, Kitui, Kenya

Correspondence: Mwobobia R.M

Correspondence: Mwobobia R.M

School of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, South Eastern Kenya

University

P O Box 170-90200, Kitui, Kenya

mmurangiri@gmail.com

Summary

The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) is a rodent that

has gained importance as a biomedical research model for various

conditions including hypoxic brain injury, cancer and nociception. It

is captured from the wild and housed under laboratory conditions

during research. Much is unknown about how to optimize housing

conditions for the animals in captivity. This study was designed to

establish whether the animals will replicate in the laboratory their

natural behaviour of having separate resting, waste disposal and

eating areas. A total of 52 naked mole rats were kept in four colonies

of different sizes and housed in two types of cage design. It was

found that, in all four colonies, their behavior was similar to that

in the wild with regards to separating their resting, eating,

defecation and urination areas. Urination and defecation commonly

occurred in the outer corners of the cages while resting and eating

mostly occurred in the inner parts of the cages. Average daily feed

consumption was 7.6 grams per naked mole rat. Weekly weight gain

averaged 0.44 grams per naked mole rat. In this study, the four

colonies of naked mole rats behaved similarly in their selection of

resting, waste disposal and eating area. However, additional studies

are needed to investigate further whether these behaviours can be

affected by colony origin, colony size or cage size. The results of

our study indicate that resting,

eating and waste disposal behaviours need to be taken into

consideration when housing naked mole rats, to optimize the comfort of

these animals in captivity.

Introduction

The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) is a subterranean rodent belonging to the family Bathyergidae. They are found in semi-arid regions of East Africa, mainly in Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia. They are eusocial (Schumacher et al. 2015; Jarvis 1981), living in colonies of up to 300 animals of overlapping generations who collectively care for the young and, in addition, show division of labour (Jarvis 1981; Susan et al. 2012).

Naked mole rats are gaining in importance for biomedical research,

being used as animal models for studies of neurodegenerative diseases,

aging, cancer, nociception, hypoxia and bioprospecting. They are

hypoxia-tolerant at the neuronal level, insensitive to acid-induced

pain and acidic fumes, are cancer resistant and long lived. These

characteristics make naked mole rats unique compared to laboratory

mice and rats (Clarke and Faulkes 1998; Kim et al. 2011; Schumacher et

al. 2015; Abiyselassie 2018). Naked mole rats housed in laboratory

conditions are shown in Figure 1, and their biological characteristics

and some environmental requirements are listed in Table 1.

Despite the use of naked mole rats in laboratory experiments, there is

still a lack of knowledge about optimal housing methods in captivity.

To create a good laboratory environment for this species, it is

necessary to study their behaviour under laboratory conditions in

relation to their behaviour in the wild. This will allow optimization

of their housing conditions, to assure well-being and correct handling

of this species, as well as the quality of the research.

Studies indicate that, in the wild, naked mole rats have separate

areas in their tunnels for resting, eating, urination and defecation

(Jarvis and Sherman 2002). This study was designed to find whether

these animals would replicate this behaviour under laboratory

conditions and if the size of the colony or cage affects this

behaviour.

|

Figure 1. Naked mole rats housed at the South

Eastern Kenya University. Click image to enlarge |

Table 1. Biology and environmental requirements of naked mole rats.

| Characteristic |

Description |

References |

Behaviour |

Eusocial rodent that lives in colonies of up to 300 animals of mixed generations |

Kress et al. 2017; Schuhmacher et al. 2015 |

Breeding |

Colony composed of a single breeding female, one to three breeding males and other hormonally suppressed colony members |

Clarke and Faulkes 1998; |

Gestation |

66-74 days |

Abiyselassie 2018 |

Litter size |

Mean litter size of 12 pups |

Buffenstein 2005 |

Body |

Cylindrical body measuring 8-10 cm long and a tail 3-5cm long |

Jarvis and Sherman 2002; Abiyselassie 2018 |

Adult weight |

30-50 grams |

Jarvis and Sherman 2002 |

Body temperature |

32°C and poikilothermic |

Schuhmacher et al. 2015 |

Longevity |

Up to 32 years |

Kim et al. 2011 |

Diet |

Roots and tubers |

Abiyselassie 2018 |

Drinking |

They solely obtain water requirements from succulent food they consume |

Jarvis and Sherman 2002 |

Habitat |

Subterranean in underground tunnels that extend up to 3 kilometres depending on food availability and colony size |

Schuhmacher et al. 2015 |

Tunnel humidity |

Up to 90% |

Schuhmacher et al. 2015 |

Tunnel temperature |

28-32°C |

Abiyselassie 2018 |

Materials & Methods

Ethical statement

The experiments were conducted after licensing (KWS/BRM/5001), and

obtaining a permit (KWS/904) to capture naked mole rats, by the Kenya

Wildlife Service (KWS) which licenses all research on wildlife in

Kenya. The study also adhered to the prevention of cruelty to animals

act, chapter 360, laws of Kenya (2012), and directive 2010/63/EU of

the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of

animals used for scientific purposes (European Union 2010).

Animals, housing and experimental design

The experiment was undertaken at the South Eastern Kenya University.

A total of 52 naked mole rats were used in the study. They were

captured from their natural burrows in Makueni County, Kenya, while

they were digging fresh mole hills (see Figure 2). Animals weighing

above 18 grams were chosen for the experiment and smaller individuals

were immediately returned to their burrows.

|

Figure 2. Mole hills at Ngaindeithia village,

Makueni County, Kenya. The mole hills are created by naked mole

rats pushing soil onto the surface while digging tunnels

underground. Click image to enlarge |

Four colonies were established for the study. The study colonies were

named according to their site of origin: Ngaindeithia A, Ngaindeithia

B, Kasaini and Darajani. Each colony was housed separately in one cage

which was also an experimental unit. Each colony was composed of naked

mole rats of both sexes in different proportions. Body weights at the

beginning of the experiment ranged between 18-41 grams, but the ages

of the animals were unknown. All animals were marked for

identification by drawing numbers on their backs using a marker pen.

Two cage sizes were built to study the effect of cage size and the

colony density on behaviour: Type 1 with 120 cm length x 40 cm width x

30 cm height (Figures 3 and 6A) and Type 2 with 70 cm length x 50 cm

width x 20 cm height (Figures 4 and 6B). Cages were made of 3 mm

diameter clear plastic acyclic glass (perspex) and they were covered

with pieces of plywood with holes to allow for ventilation.

|

Figure 3. Cage Type 1: 120 cm length x 40 cm

width x 30 cm height, the floor area was 4800 cm2. The cage was

divided into three compartments. Click image to enlarge |

|

Figure 4. N Cage Type 2: 70 cm length x 50 cm

width x 20 cm height, the floor area was 3500 cm2. The cage was

divided into three compartments. Click image to enlarge |

Table 2. Colony housing details

| Colony |

Ngaindeithia A |

Darajani |

Kasaini |

Ngaindeithia B |

Animal number in colony |

20 |

15 |

10 |

7 |

Cage type |

1 (4800 cm2) |

1 (4800 cm2) |

2 (3500 cm2) |

2 (3500 cm2) |

Space/animal |

240 cm2 |

320 cm2 |

350 cm2 |

500 cm2 |

|

Total weight of the colony at the beginning |

652.6 g |

492.7 g |

324.2 g |

219.8 g |

|

The mean weights of animal at the beginning |

32.63 ± 4,4 g |

32.85 ± 5,9 g |

32.42 ± 6,0 g |

31.40 ± 5,7 g |

The cages were divided by partitions into three compartments to simulate the natural habitat and the tunnel structures of the naked mole rats, giving them opportunity to use separate areas for different behaviours. The partitions are shown in Figures 3 and 4 and indicated by lines in Figures 6A and 6B. The partitions and outer sides of the cages were opaque during the experiments; the cage in Figure 4 was covered on the outer side with opaque material during experimentation period. This was to mimic an underground burrow with solid earthen walls.

The four colonies had a different number of naked mole rats. Colonies

Ngaindeithia A (n=20) and Darajani (n=15) were housed in Cage Type 1

and Kasaini (n=10) and Ngaindeithia B (n=7) in Cage Type 2. The floor

area per individual animal and the total weight of the colony at the

beginning of the experiment are shown in Table 2.

The cage bedding consisted of wood shavings of fine texture made from

local trees; was not pre-treated with any chemicals and was changed

weekly. The cage bedding was about 2.5 cm deep. No additional

materials were provided in the cage.

Temperature in the animal room was maintained at 28-31°C, to simulate

the temperature in the animals’ natural burrows. Humidity was

maintained at 50-70% to prevent drying and scaling of the mole rat

skin. Both temperature and humidity in the room were measured by a

thermo hygrometer (Brannan, England). Room temperature was maintained

by the use of two 250 watt infrared lamps (Euro-matt) and a fan heater

(1500 watts, Intertronic, UK). By blowing hot air, the fan heater

assisted evaporation of water from plastic basins, thus raising

humidity levels.

The light-dark cycle in the animal room was 12/12, with lights on from

06.00 to 18.00 hours. Ventilation of the cages was achieved by

covering them with plywood that had 3 holes each of 2 cm diameter

(each aligned per cage compartment) to allow circulation of air. The

plywood cover was also not closely fitting. The animal room with cages

and other equipment is shown in the Figure 5.

|

Figure 5. The animal room showing placement of

various items: the four naked mole rat colonies (c1-c4),

infrared lamps (IR), thermo hygrometer (T), fan heater (FH),

water basins (WB). Click image to enlarge |

Feeding and food consumption

Animals were provided with food chopped into pieces of about 1 cm,

which made it necessary for the animals to spend time chewing the

food. Enough food was provided to allow ad libitum consumption such

that there was always uneaten food remaining the following day. Since

each cage had three compartments, food was placed in the middle of

each compartment sequentially during the experimental period. The diet

consisted of fresh carrots, sweet potatoes and Irish potatoes. There

was no pre-treatment of the food except for washing in clean water.

Animals were fed daily at around 09.00 am after measuring food

remaining from the previous day and observing their behaviour. No

water was provided since the animals obtain their water requirements

from their succulent diet (Jarvis and Sherman 2002).

To calculate the food consumed in each cage, the remaining food was

subtracted from the food provided, taking a factor for environmental

moisture loss into consideration, i.e. the food consumed was

calculated as amount fed - remaining food - environmental moisture

loss. Environmental moisture loss was averaged at 22.2% and was

calculated by leaving a known amount of food undisturbed in the same

room with naked mole rats and weighing it again after 24 hours. The

loss in weight was attributed to moisture loss to the environment.

Food consumption was investigated for 28 days.

|

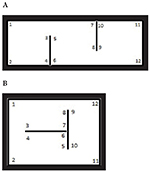

Figure 6. Cage type 1 (A) and cage type 2 (B)

seen from aerial view. The lines inside both cage types are

partitions dividing the cages into three compartments. Numbers

1-12 in each cage show the points where behavioural observations

were made, i.e. urination, defecation, eating and resting

behaviours. The points were classified as either outer corners

(points 1, 2, 11 and 12) or inner areas (points 3-10). Click image to enlarge |

Statistical analysis

Food consumption data were analysed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s

multiple comparison tests. Weight gain among the four colonies was

analysed using one way ANOVA tests while the t-test was used to

compare weight gain between large and small colonies. Both ANOVA and

t-test were carried out using Graph Pad Prism 5.0. Chi-square test was

used to analyse behavioural observations.

Results

Naked mole rat weights

Weekly weight gain averaged 0.44 g per animal. The iincrease in total

animal weight per colony from the beginning to the end of the

experiment was 34.7 g (Kasaini), 28.5 g (Darajani), 21.4 g

(Ngaindeithia A) and 17.4 g (Ngaindeithia B). Kasaini colony had the

highest (median and mean) weight gain while Ngaindeithia A colony had

the lowest (median and mean) weight gain as well as the smallest

variation in weights (Figure 7A). However, there was no significant

difference in weight gain between the four colonies and there was no

significant difference in weight gain between small and large colonies

(Figure 7B).

|

Figure 7. Scatter plots at each colony

represents means of individual animal weight at days 1, 7, 14,

21 and 28. Horizontal bars on the scatter plots represent

overall mean of the individual weights for the entire

experimental period. Figure 7A shows scatter plots of mean

individual weights for the four colonies. Figure 7B shows

scatter plots of mean individual weight for the colonies grouped

into either big colonies i.e. Darajani (n=15) and Ngaindeithia A

(n=20) or small colonies i.e. Kasaini (n=10) and Ngaindeithia B

(n=7). Click image to enlarge |

Food consumption

The average daily food consumption per naked mole rat was 7.6 grams

after factoring environmental moisture losses of 22.2% per day

(Ngaindeithia A=6.4 grams, Darajani=7.2 grams, Kasaini=7.8 grams and

Ngaindeithia B=9.1 grams). Environmental moisture loss was associated

with the animal room temperatures kept above 28°C. Weekly food

consumption per individual naked mole rat in Ngaindeithia B colony

exceeded that in other colonies. Large colonies (Ngaindeithia A and

Darajani) consumed significantly less (P < 0.05) food per week

compared to Ngaindeithia B colony (Figure 8).

|

Figure 7. Box and whisker plots showing weekly

food consumption (in grams) per naked mole rat in each of the

four colonies. The whiskers outside the boxes represent minimum

and maximum values while lines within the boxes represent median

values. Click image to enlarge |

Behavioural observations

The animals were consistent by undertaking a particular behaviour, for

example urination, around a particular site in the cage and did not

use other sites. Hence every day, each behaviour was recorded at one

site which was either an outer corner or inside area of the cage. Thus

on each day there was just one data point per behaviour per colony.

Urination and defecation occurred mostly at the outer corners (points

1, 2, 11 and 12) while resting and eating occurred predominantly at

the inner areas (points 3-10) of the cages (See Figures 6 A and B).

Although the Darajani colony had more defecation recorded at the inner

areas of the cage than the other colonies (p = 0.035, chi square

test), most defecation occurred at the outer corners. Thus, in all

colonies, the pattern of separating toilet (urination and defecation)

from eating and resting areas occurred irrespective of colony size or

cage design (Figure 9).

|

Figure 9. Box and whisker plots showing the

location of the toilet, eating and resting behaviours,

classified as either outer corners of the cages (points 1, 2, 11

and 12) or inside areas of the cages (points 3 to 10). For all

colonies, each behaviour was counted once a day for 20 days. The

number of times a behaviour was recorded on the inner or outer

areas is shown on the vertical axis. The whiskers outside the

boxes show minimum and maximum counts for the particular

behaviour while lines within the boxes show the medians. Click image to enlarge |

Discussion and conclusion

The European Union directive 2010/63 (European Union 2010), emphasizes refinement of accommodation and care of laboratory animals to reduce animal suffering and distress. The directive also advises on accommodation and care of animals based on specific needs and characteristics of each species. Similar emphasis is expressed in the FELASA (Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations) report on provision of environmental enrichments through complexity, resting and bedding facilities to allow for species specific behaviours and reduce experimental variability (FELASA 2006).

This study was designed to find out whether captive naked mole rats

can replicate in the laboratory their natural behaviour in the wild of

having separate resting, waste disposal and eating areas.The animals

were housed at a room temperature between 28 to 31oC and humidity of

50-70%. They were kept in ventilated cages with three compartments and

provided with fine wood shavings for bedding and resting, and food

consisting of fresh carrots and potatoes. These conditions were

designed to simulate the environmental conditions in nature as

reported by Schumacher et al. (2015) where they live in an underground

network of chambers and tunnels, with temperatures ranging between 28

to 32oC depending on tunnel depth, high humidity levels of up to 90%,

and feed on roots and tubers.

In the laboratory, all four naked mole rat colonies had eating and

resting areas separated from waste disposal areas (defecation and

urination). Resting and eating sites were found to be at the same

place or adjacent to each other, but separate from urination and

defecation sites, which were also at the same place or adjacent to

each other. This behaviour reflects that seen in the wild, where naked

mole rats are reported to urinate and defecate only in the toilet

chamber to avoid contamination. In addition, the animals dig new sites

for urination and defecation if the old ones become full (Jarvis and

Sherman 2002; Rosamond Gifford Zoo 2006). A study by Margullis et al.

(1995) observed the same behaviour in captive naked mole rats which

also separated eating sites from urination and defecation sites.

The observation that naked mole rats in small colonies consumed more

food but without a significant difference in weight gain compared to

the naked mole rats in large colonies indicates they may have been

more active and therefore expended more energy. The finding that there

was no significant difference in weight gain between the four

colonies, suggests that the number of naked mole rats per cage may not

influence weight gain. During the experiment, the naked mole rats were

fed on a diet of fresh sweet potatoes, carrots and Irish potatoes. The

observed weekly weight gain of 0.44 g per naked mole rat indicates

this diet is suitable for use in the laboratory. In both wild and

captive conditions, they feed on roots, tubers and bulbs such as sweet

potatoes, Irish potatoes, grapes, apples, bananas and other succulent

plant material (Rosamond Gifford Zoo 2006; Judd and Sherman 1996;

Jarvis and Sherman 2002). The animals also practice coprophagy to

maximize extraction of nutrients from their food (Abiyselassie 2018).

Since there is a lack of data on standard housing of the naked mole

rat under laboratory conditions, the findings of this study provide an

initial recommendation of how to house the naked mole rat. These

findings are open for further improvement, but already fulfil the

intentions of EU directive 2010/63 (European Union 2010).

Based on this study, it is recommended that captive naked mole rats

should be provided with cages designed to allow them to maintain

separate locations for waste disposal (urination and defecation),

resting and eating. This is an important consideration to increase

comfort and well-being of these animals in the laboratory. However,

additional studies are needed to investigate further the effect of

colony size, colony origin and cage size on naked mole rats’ behaviour

in captivity.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Copenhagen for

providing grants to facilitate the completion of the study, as well as

the South Eastern Kenya University for providing the research

infrastructure needed. The authors would also like to express

gratitude to Gilbert Mwanthi for taking care of the animals.

The authors received generous assistance in data analysis by Dr. Gerit

Pfuhl, UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abiyselassie, G.A., (2018). Overview of African naked mole-rat Heterocephalus glaber for bioprospecting and access and benefit sharing in Ethiopia. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 4(1), 25-37. doi:10.30574/gscbps.2018.4.1.0042

- Buffenstein, R., (2005). The naked mole-rat: A new long-living model for human aging research. Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences. 60(11), 1369–1377.

- Clarke, F.M., Faulkes, C.G. (1998). Hormonal and behavioural correlates of male dominance and reproductive status in captive colonies of the naked mole-rat, Heterocephalus glaber. Proceedings. Biological sciences. 265(1404), 1391–1399. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1998.0447

- European Union, (2010). Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Official Journal of the European Union L276/33. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:276:0033:0079:EN:PDF

- FELASA Standardization of Enrichment Working Group Report, (2006) http://www.felasa.eu/working-groups/reports/standardization-of-enrichment/

- Imberman, S.P., Kress, M., McCloskey, D.P., (2012). Using Frequent Pattern Mining to Identify Behaviors in a Naked Mole Rat Colony. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference.

- Jarvis, J.U.M., (1981). Eusociality in a mammal: Cooperative breeding in naked mole-rat colonies. Science. 212(4494), 571-573.

- Jarvis, J.U.M., Sherman, P.W., (2002). Heterocephalus glaber. Mammalian Species. (706), 1–9.

- Judd, M., Sherman, W., (1996). Naked mole-rats recruit colony mates to food sources. Animal Behaviour. (52), 957–969.

- Kim, E.B. et al., (2011). Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature. (479), 223. doi:10.1038/nature10533

- Kress, M., Meehan, E.F., McCloskey, D., (2017). Large-scale surveillance of captive naked mole-rat colonies shows caste differences in space utilization. Working Paper. CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/si_pubs/102/.

- Margullis, S.W., Saltzman, W., Abborrt, D.H., (1995). Behavioral and hormonal changes in female naked mole-rats. Hormones and behaviour. (29), 227-247.

- Prevention of cruelty to animals act, Chapter 360, laws of Kenya, Revised edition 2012 [1983] http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ken63702.pdf

- Rosamond Gifford Zoo (2006). Naked mole rat (online), Available at http://www.rosamondgiffordzoo.org/assets/uploads/animals/pdf/NakedMoleRat.pdf

-

Schumacher, L., Husson, Z., Smith, E.S., (2015). The naked mole-rat

as an animal model in biomedical research: current perspectives.

Open Access Animal Physiology. (7), 137–148.

https://doi.org/10.2147/OAAP.S50376