Original scientific article

Establishment of mutant mouse strain showing eosinophilia

By Yusuke Yamada11, Keisuke Okamoto1, Masashi

Sakurai1, Yusuke Sakai1, Moe

Hasegawa1, Hiroyuki Imai3, Shusaku

Shibutani4, Masahiro Morimoto1

1

Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology, Joint Faculty of Veterinary

Medicine, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan.

2

National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan.

3

Laboratory of Veterinary Anatomy, Joint Faculty of Veterinary

Medicine, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan.

4

Laboratory of Veterinary Hygiene, Joint Faculty of Veterinary

Medicine, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi, Japan.

Correspondence:

Masahiro MorimotoLaboratory of Veterinary Pathology, Joint Faculty

of Veterinary Medicine, Yamaguchi University, 1677-1, Yoshida,

Yamaguchi 753-8515, Japan. Tel: +81-083-933-5892, Fax:

+81-083-933-5892

E-mail:

morimasa@yamaguchi-u.ac.jpk

Summary

Eosinophilia is a pathological condition characterized by an increased number of eosinophils in tissues and peripheral blood. The type 2 immune response causes eosinophilia, and interleukin-5 (IL-5) secreted by T helper 2 (Th2) cells is essential for increasing eosinophils. However, it is unclear whether there is another mechanism for an increase in eosinophils. The present study found high numbers of eosinophils in ICR mice and established an inbred strain with hypereosinophilia, named “Yama mouse”, through brother-sister mating. Eosinophil count in the peripheral blood of 6-week-old Yama mice was 30-fold higher than in ICR mice of the same age, but hyperkeratisation of the stomach was the only lesion observed in Yama mice. There was no significant difference between ICR and Yama mice in IL-5 expression in the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes or bone marrow. Yama mice revealed a mechanism for increased eosinophil counts other than that of IL-5 upregulation. Yama mice exhibit eosinophilia without artificial treatment; therefore, they are a good animal model for studying allergic diseases and regenerative medicine, in which eosinophils are important.

Introduction

Eosinophilia is a pathological condition characterized by increased

numbers of eosinophils in tissues and peripheral blood (Kovalszki

2016). Eosinophilia is caused by various diseases, such as allergies,

helminthic infections and idiopathic causes of unknown etiology

(Kovalszki 2016). The type 2 immune response causes eosinophilia, and

interleukin-5 (IL-5) secreted by T helper 2 (Th2) cells is essential

for the increase in eosinophils (Nagase et al. 2020; Nussbaum et al.

2013). However, few studies have investigated the mechanism of

increased eosinophil levels downstream of IL-5 receptors other than

the role of GATA-1. Additionally, it is unclear whether there is a

mechanism to increase the eosinophil count other than via IL-5 signal

transduction.

Furthermore, there are several experimental animal models for

eosinophilia, such as the helminth infection (Kusama et al. 1995),

hypersensitivity (McMillan et al. 2014), and IL-5 transgenic mouse

models (Masterson et al. 2014) exhibiting eosinophilia owing to

increased IL-5 expression (Kusama et al. 1995; McMillan et al. 2014;

Masterson et al. 2014). However, the mechanisms downstream of the IL-5

receptor, other than the role of GATA-1, have not been determined,

probably because in the helminth infection and hypersensitivity

models, there are significant differences between individuals in the

number of eosinophils, and investigation of the mechanism is complex

and time-consuming (Kusama et al. 1995; Rayapudi et al. 2010). The

IL-5 transgenic mouse model is a cytokine gene manipulation model that

overexpresses IL-5. However, in transgenic mice the genomic

environment at the integration site substantially influences the

expression of the randomly inserted transgene (Liu. 2013), suggesting

that IL-5 activation in transgenic mice may differ between

individuals. Experiments investigating airway immune responses in

asthma models using different IL-5 transgenic mice have provided

contrasting results (Lee et al. 1997; Kobayashi et al. 2003). Thus,

the helminth infection, hypersensitivity and IL-5 transgenic mouse

models are unsuitable for investigating eosinophil-stimulating factors

downstream of the IL-5 receptor.

Additionally, it is unclear whether mechanisms other than IL-5 signal

transduction increase the number of eosinophils. There are currently

no animal models of eosinophilia without IL-5 upregulation. Therefore,

there is need for models to investigate other possible mechanisms of

increasing eosinophil count, probably through the upregulation of

mechanisms other than IL-5 signal transduction or the upregulation

downstream IL-5 receptors.

We established an inbred mouse strain exhibiting peripheral blood

eosinophilia without IL-5 overexpression, providing an opportunity to

investigate eosinophil-stimulating factors other than IL-5. In the

present study, we report the kinetics of eosinophil counts, IL-5, IL-4

and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expression in the spleen, bone marrow and

mesenteric lymph node, and histological examinations.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six-week-old ICR mice were purchased from SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan;

they were specific-pathogen-free (JALAS: Japanese Association for

Laboratory Animal Facilities of National University Corporation

recommendations). Untreated females exhibiting high eosinophil counts

in peripheral blood were mated with their male parent. A high blood

eosinophil level was regarded as more than 264/µl, which was the mean

± 2 standard deviation of the mean (SDM) of blood eosinophils in

normal ICR mice. After weaning the second-generation litter, we

counted the number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood, and

individuals with a high number of eosinophils were repeatedly mated

with sisters and brothers for >20 generations to establish an inbred

mouse strain (Yama mouse).

Yama mice can breed normally, and they survive for at least one and a

half years. Yama mice show no difference in development and weight

compared to control ICR mice at 6-weeks, but as the get older, they

are slightly heavier because they have slightly more fat tissue. The

white blood cell counts other than eosinophils and the red blood cell

counts were normal, and no gross abnormalities were noted in any

identifiable organs.

The ICR and Yama mice were maintained at ARCLAS (Advance Research

Center for Laboratory Animal Science of Yamaguchi University) in a

conventional area with periodic pathogen monitoring tests within the

same part of the SPF facility, accredited by the American Association

for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The animal room was

maintained at 24 ± 2 ℃ and 50–70% humidity under an artificially

illuminated light and dark cycle (12:12 h Light: Dark cycle). Mice had

ad libitum access to a standard laboratory diet (CE-2 commercial

compound diet for mice, Clea Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and tap water.

Mice were housed in cages of CL-0138 (M-2: Japan Clea W184xD332xH147)

with Eco Chip™ (Japan Clea) as bedding material and a mouse igloo.

Three to four animals were housed per cage. During the gestation

period, they were housed individually.

All experimental procedures were conducted following the guidelines

for animal experiments at Yamaguchi University, Japan, with the

approval of the Animal Research Committee (permit number 401).

Sampling and tissue preparation

Blood samples were collected from 6- and 18-week-old ICR and Yama mice. Briefly, each mouse was anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of 10 mg/kg xylazine (Bayer, Tokyo, Japan) and 80 mg/kg ketamine (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus using a capillary tube (AS ONE Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Whole blood samples were collected from the mice after anesthesia. Serum samples were obtained after centrifugation (3000 rpm, 10 min). For tissue sampling, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation when 6-weeks old, and the organs (stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, heart, lungs, kidneys, spleen, bone marrow and mesenteric lymph nodes) were immediately removed. RNA was extracted from the spleen, bone marrow and mesenteric lymph nodes and subjected to a reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Organs were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MA, USA) for histopathological examination. After fixation, the unilateral femur was decalcified with 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA solution [Sigma Aldrich]) at pH 7.0 for 24 h for histopathological examination of the bone marrow. The samples were then routinely embedded in paraffin, and 4-µm-thick sections were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining (Abbey Color Inc., ST Tioga, PA, USA). Bone marrow sections were prepared for immunohistochemistry for counting eosinophils.

Blood and tissue eosinophil count

The number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood was counted after staining with Hinkelman’s solution, as previously reported (Morimoto et al. 1998). The eosinophils were counted under a microscope using a hemocytometer (Tatai eosinophil counter [Kayagaki Irikakogyo Co., Tokyo, Japan]). Bone marrow sections were stained with H & E (Abbey Color Inc.) and immunohistochemistry was performed using an eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, ECP immunohistochemistry was performed using rabbit anti-mouse ECP IgG (1: 400 [Aviscera Bioscience, Inc. Santa Clara, CA, USA]). ECP-positive cells were counted in five fields of view under an optical microscope at 100x magnification, and the number of ECP-positive cells as a percentage of total cells was calculated.nized with an overdose of pentobarbitone (100 mg/kg, IV).

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted from the bone marrow, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of 6-week-old ICR and Yama mice using an RNeasy 2012 extraction kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were transcripted by incubating at 37 ℃ for 60 min, 95 ℃ for 5 min, and on ice for 5 min to create cDNA using a ReverTra Ace kit (TOYOBO CO., Osaka, Japan). For the quantification of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA, 4 µL of cDNA samples were amplified using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (IFN-γ: Mm01168134_m1, IL-4: Mm00445259_m1, IL-5: Mm04239646_m1 [Life Technologies Japan Ltd, Tokyo, Japan]) using a Step One real-time PCR system (Life Technologies Japan Ltd). Amplification was done at 50 cycles of 50 ℃ for 2 min, 95 ℃ for 10 min, 95 ℃ for 15 s, and 60 ℃ for 1 min. 18s rRNA (Mm03928990_g1 [Life Technologies Japan Ltd]) was used as a housekeeping (reference) gene and subjected to IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 standardization.

ELISA

Serum IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 from ICR and Yama mice was quantified using an ELISA kit (IFN-γ, IL-4: Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan., IL-5: Funakoshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression levels of the cytokines were determined by comparison to a standard curve generated by serial dilution of manufacturer-provided standard. The T helper 1 (Th1) to Th2 ratios were calculated by IFN-γ/IL-4 in ICR and Yama mice.

Statistical analysis

Significant differences were tested using Student’s t-test (p<0.05). Data were presented as the mean ± SDM.

Results

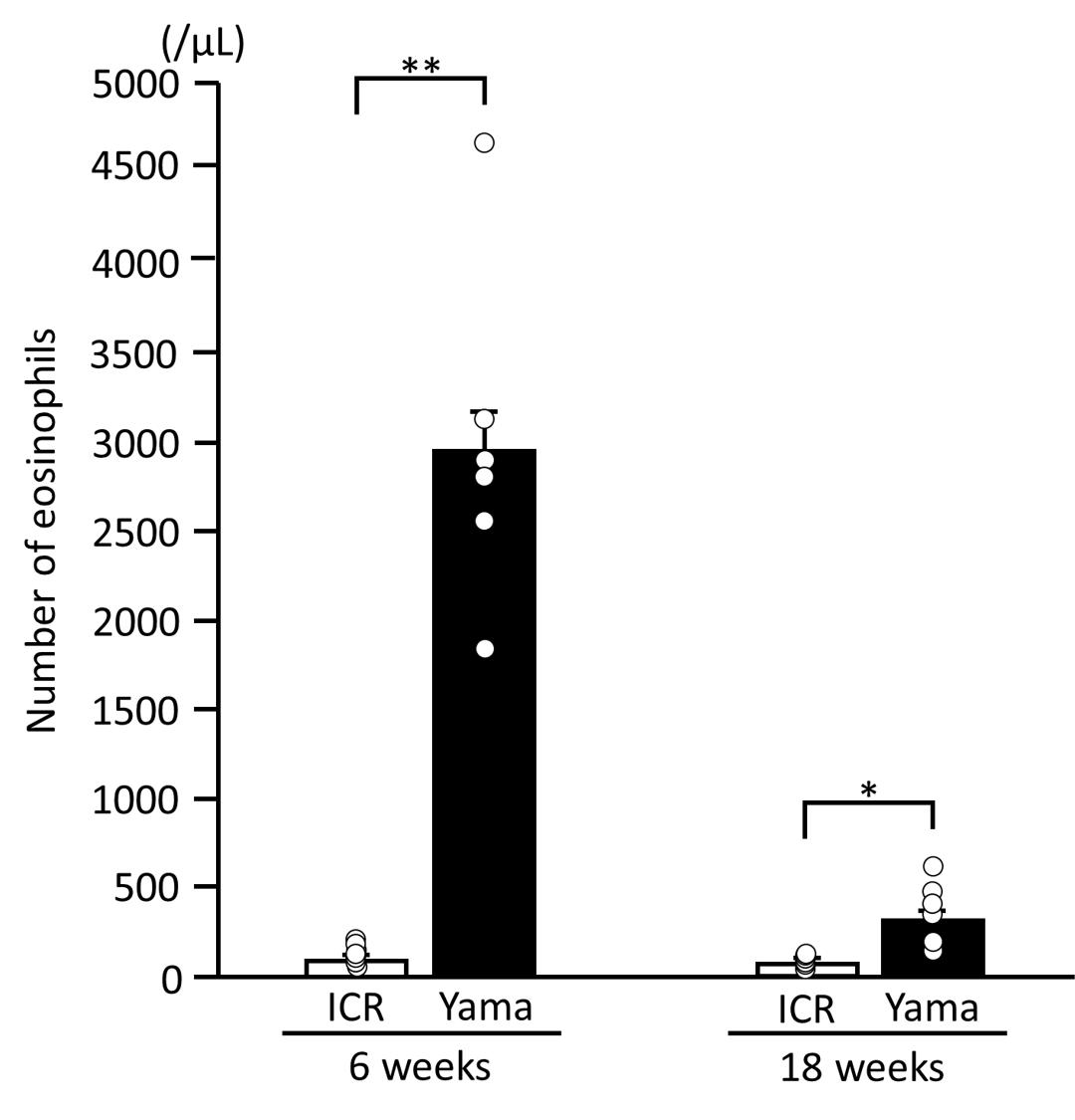

Blood eosinophils

Figure 1 presents the number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood of 6- and 18-week-old ICR and Yama mice. The number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood of 6-week-old Yama mice was 30-fold higher than that of 6-week-old ICR mice. The number of eosinophils in 18-week-old Yama mice decreased to approximately 1/10 of that in 6-week-old Yama mice, but was still 4-fold higher than that in 18-week-old ICR mice.

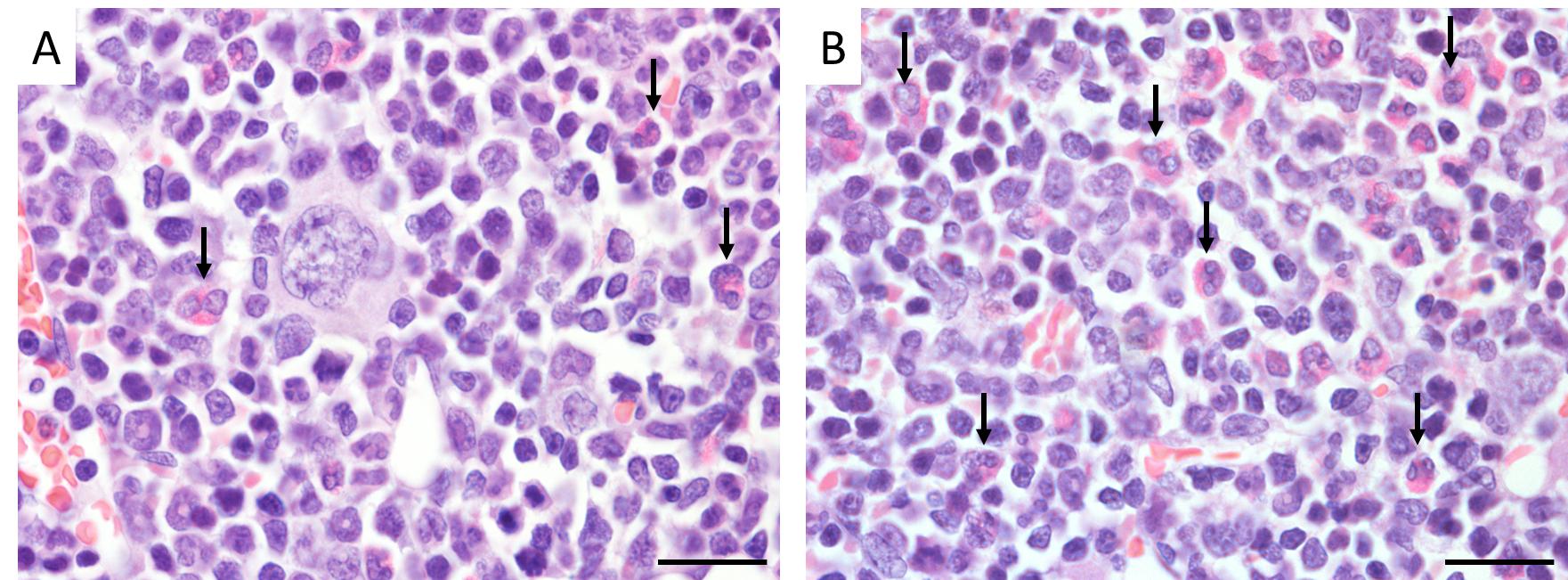

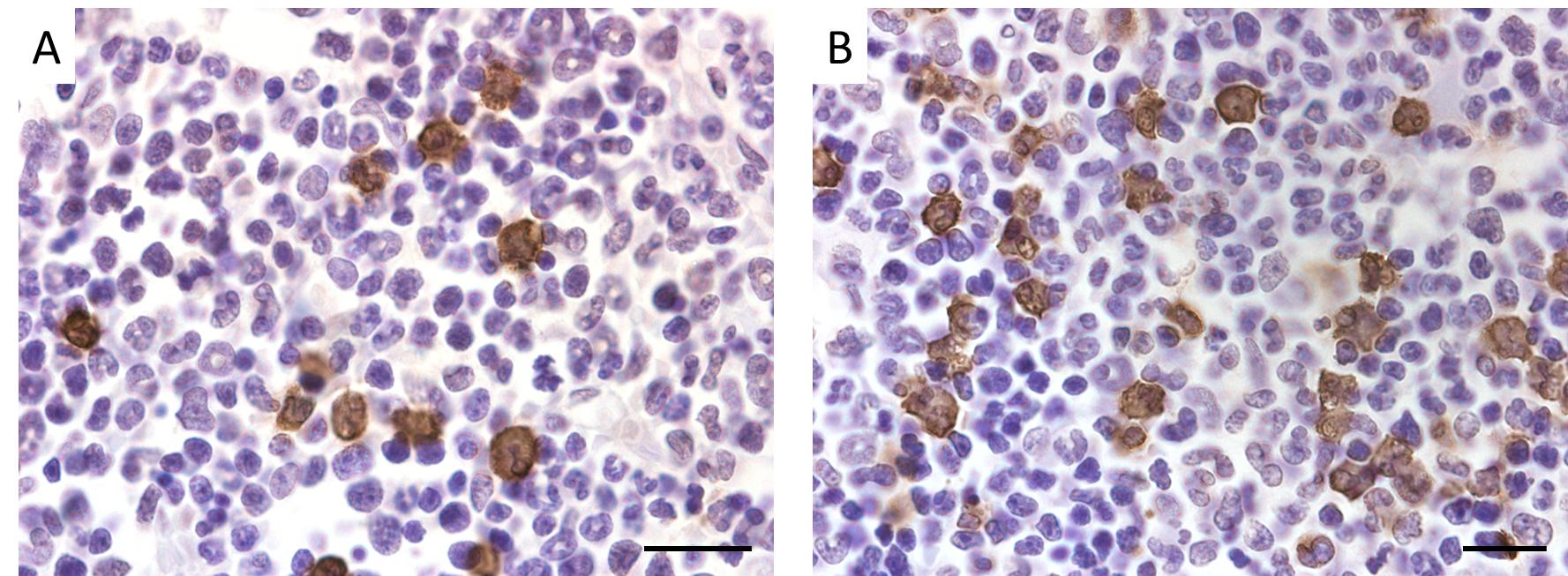

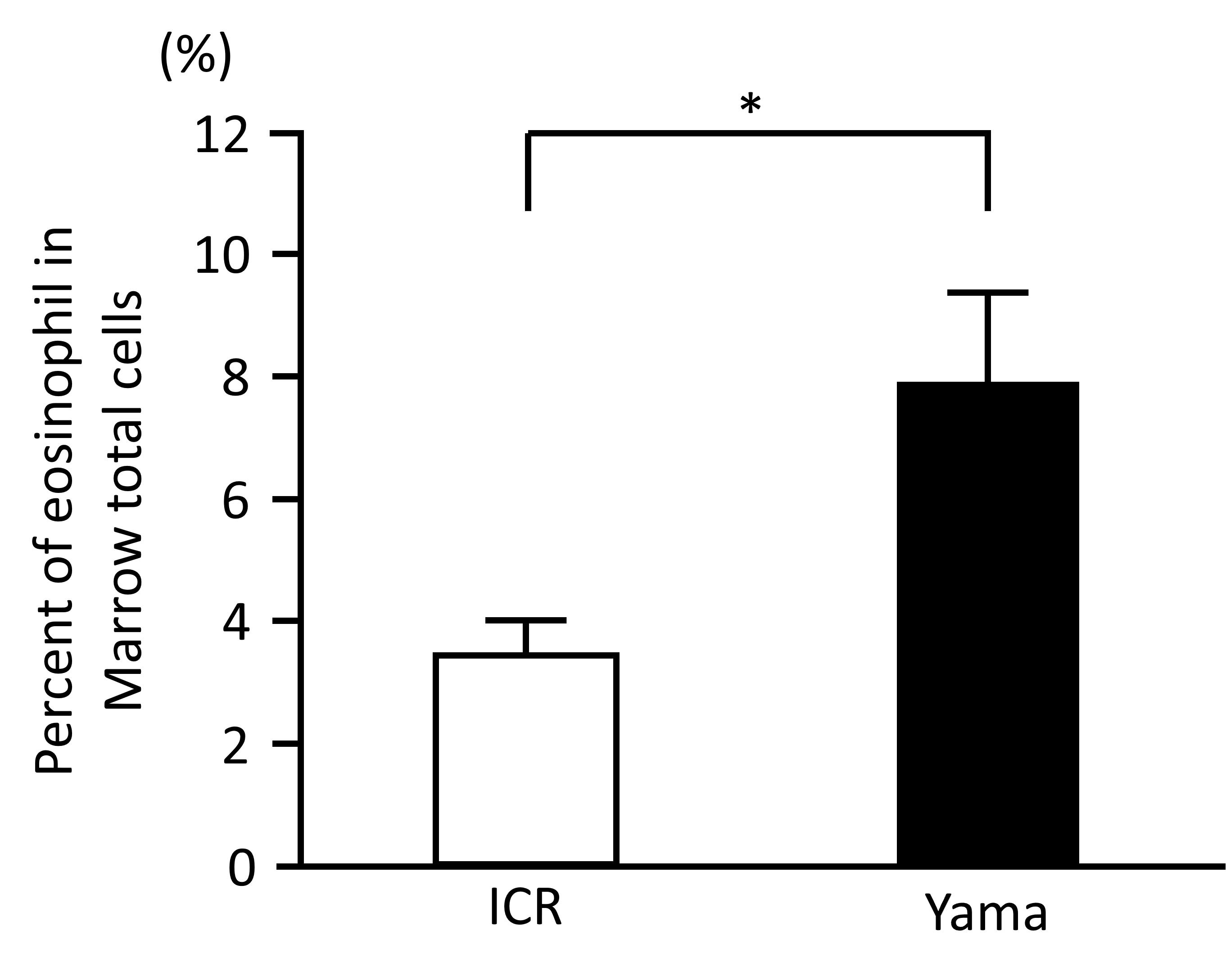

Histological analysis

Eosinophils were identified by a segmented nucleus and cytoplasmic eosinophilic granules in H & E staining of bone marrow samples (Figure 2) and confirmed by immunopositivity in ECP immunohistochemistry (Figure 3). In H & E staining and ECP immunohistochemistry, eosinophils were more numerous in Yama mice than in ICR mice. The percentage of eosinophils in ECP immunohistochemistry of bone marrow was significantly higher in Yama mice (7.93 ± 2.34%) than in ICR mice (3.54 ± 0.43% [Figure 4]). Hyperkeratinization was observed in the squamous epithelium of the stomach of 6-week-old Yama mice, but no lesions were observed in the other organs examined histologically.

Cytokine expression

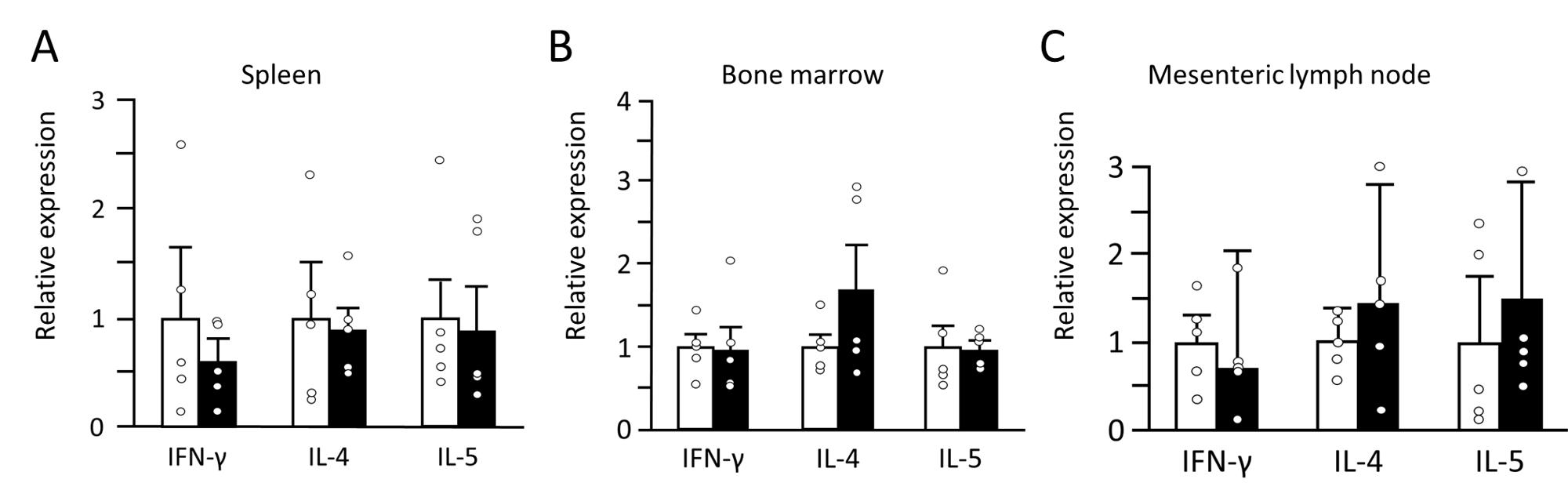

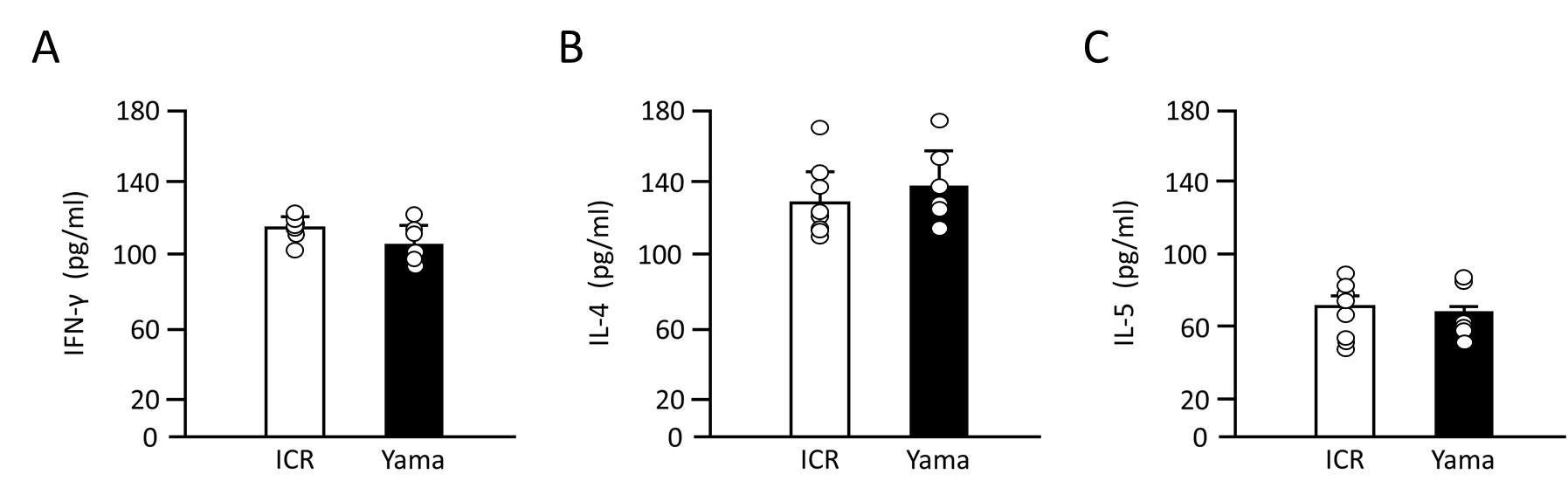

The mRNA expression levels of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 in tissues are presented in Figure 5. There was no significant difference between ICR and Yama mice in IL-5 IL-4 or IFN-y expression in the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes or bone marrow. The serum IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-5 levels are presented in Figure 6. The levels of all these cytokines in the serum were not significantly different between ICR and Yama mice. The Th1 to Th2 ratio in the serum of ICR and Yama mice was approximately 1:1.15 and exhibited almost the same value.

Discussion

In the present study, we established for the first time a new mutant inbred mouse that exhibited spontaneous eosinophilia.

IL-5 is important for eosinophil activation and proliferation (Nagase et al. 2020). In previous studies, several animal models exhibited eosinophilia and increased IL-5 mRNA expression (Farzaneh et al. 2006; Kusama et al. 1995; Masterson et al. 2014). Although Yama mice exhibited eosinophilia, there was no significant difference in IL-5 mRNA expression between Yama and ICR mice in the spleen, bone marrow and mesenteric lymph nodes, and this was consistent with next-generation RNA sequencing (data not presented). In addition, there was no significant difference in serum IL-5 level between Yama and ICR mice. These results indicate that eosinophilia in Yama mice is caused by factors other than IL-5. There are three possible mechanisms for causing eosinophilia in Yama mice. Firstly, stimulation of downstream IL-5 signal transduction. Secondly, stimulation of a signaling cascade for eosinophil activation caused by factors other than IL-5 signal transduction. Thirdly, dysfunction of suppressor molecules of eosinophil activation, possibly owing to the upregulation of a molecule downstream of IL-5 signal transduction. However, downstream of the IL-5 signaling cascade is unknown, except for the involvement of the transcription factor GATA-1 (Hirasawa et al. 2002) in cells such as erythrocytes and mast cells. Increased GATA-1 expression, leads to symptoms such as jaundice or splenomegaly as transient abnormal myelopoiesis in mice (Garnett et al. 2020). However, these symptoms were not observed in Yama mice, suggesting that the mutation downstream of the IL-5 signaling cascade involves a molecule other than GATA-1. The second possibility is an unknown signaling cascade, suggesting that eosinophilia in Yama mice is due to a new mechanism that increases eosinophils. In the first two possibilities gene mutations cause upregulation of the molecule that induces eosinophilia production. In the third possibility the mutated molecule suppresses the Th2 immune response; activation of eosinophils is correlated with the Th2 immune response.

The number of peripheral eosinophils in Yama mice was significantly higher than in the ICR mice at 6 and 18 weeks. However, the number of eosinophils in 18-week-old Yama mice was lower than that in 6-week-old Yama mice. This is difficult to explain if the mutation in the Yama mouse enhances the activity of the molecule that induces an increase in eosinophils. The Th1 immune response involves several suppressor molecules that have similar functions (Li et al. 2015; Parry et al. 2005). The suppressor molecule in the Th2 immune response is unknown; if there are several Th2 suppressor molecules and these factors act like the Th1 system, one possible explanation is that mutation of Yama mice decreases the activity of some of these molecules, and that with time other molecules compensate for the decreased activity. This hypothesis is the most likely explanation for the results of the present study. However, it is necessary to further investigate Yama mice to identify factors associated with eosinophilia production. Suppose the mutated molecule is a Th2 suppressor molecule; it will be the first Th2 suppressor molecule known to have the potential to become a target molecule for the treatment of Th2-related diseases, such as allergy and fibrotic disease (Wynn. 2004), ulcerative colitis (Nemeth et al. 2017) and idiopathic eosinophilia.

Eosinophils are thought to regulate conditions such as liver (Goh et al. 2013) and muscle regeneration (Liu et al. 2020; Heredia et al. 2013) and wound healing (Wong et al. 1993; Todd et al. 1991). However, the detailed mechanisms underlying the function of eosinophils have not been elucidated owing to a lack of good models. To investigate the details of these eosinophil functions in vivo, models in which eosinophils are increased without causing lesions are needed. The helminth infection model is most commonly used to investigate eosinophil functions (Kusama et al. 1995). However, it is not suitable for investigating eosinophils in detail because their function is affected by helminth infection-induced lesions. The histological results in Yama mice did not reveal any lesions, except for hyperkeratosis of the stomach. Yama mice are novel mutant mice established as an inbred strain expressing eosinophilia, and each Yama mouse stably exhibited similar phenotypic expression. Furthermore, it is possible to observe the activity of eosinophils more closely in vivo using Yama mice without considering the effect of lesions caused by treatment because Yama mice exhibit eosinophilia without artificial treatment.

There were no significant differences between Yama and ICR mice in the expression of the cytokines IL-5, IL-4 and IFN-γ in the spleen, bone marrow and mesenteric lymph nodes or in serum. In addition, the Th1/Th2 ratio is almost the same in Yama and ICR mice. These results suggest that the increase in eosinophils in Yama mice is not caused by the activation of the Th2 immune response.

Yama mice are the best model for studying eosinophilia, and the investigation of eosinophilia in Yama mice will lead to progress in the study of idiopathic eosinophilia. Moreover, Yama mice can be a good animal model for studying allergies and regenerative medicine, in which eosinophils are important (Kitamura et al. 2018; Heredia et al. 2013).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2111.

References

- Farzaneh, P., Hassan, Z.M., Pourpak, Z., Hoseini, A.Z., Hogan, S.P., (2006). A latex-induced allergic airway inflammation model in mice. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 99(6), 405-411.

- Garnett, C., Hernandez, D.C., Vyas, P., (2020). GATA1 and cooperating mutations in myeloid leukaemia of Down syndrome. IUBMB Life. 72(1), 119-130.

- Goh, Y.P., Henderson, N.C., Heredia, J.E., Eagle, A.R., Odegaard, J.I., Lehwald, N., Nguyen, K.D., Sheppard, D., Mukundan, L., Locksley, R.M., Chawla, A., (2013). Eosinophils secrete IL-4 to facilitate liver regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110(24), 9914-9919.

- Heredia, J.E., Mukundan, L., Chen, F.M., Mueller, A.A., Deo, R.C., Locksley, R.M., Rando, T.A., Chawla, A., (2013). Type2 innate signals stimulate fibro/adipogenic progenitors to facilitate muscle regeneration. Cell. 153(2), 376-388.

- Hirasawa, R., Shimizu, R., Takahashi, S., Osawa, M., Takayanagi, S., Kato, Y., Onodera, M., Minegishi, N., Yamamoto, M., Fukao, K., Taniguchi, H., Nakauchi, H., Iwama, A., (2002). Essential and instructive roles of GATA factors in eosinophil development. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 195(11), 1379-1386.

- Kitamura, A., Takata, R., Aizawa, S., Watanabe, H., Wada, T., (2018). A murine model of atopic dermatitis can be generated by painting the dorsal skin with hapten twice 14 days apart. Scientific Reports. 8(1), 5988.

- Kobayashi, T., Iijima, K., Kita, H., (2003). Marked airway eosinophilia prevents development of airway hyper-responsiveness during an allergic response in IL-5 transgenic mice. The Journal of Immunology. 170(11), 5756-5763.

- Kovalszki, A., Weller, P.F., (2016). Eosinophilia. Primary Care. 43(4), 607-617.

- Kusama, M., Takamoto, M., Kasahara, T., Takatsu, K., Nariuchi, H., Sugane, K., (1995). Mechanisms of eosinophilia in BALB/c-nu/+ and congenitally athymic BALB/c-nu/nu mice infected with Toxocara canis. Immunology. 84(3), 461-468.

- Lee, J.J., McGarry, M.P., Farmer, S.C., Denzler, K.L., Larson, K.A., Carrigan, P.E., Brenneise, I.E., Horton, M.A., Haczku, A., Gelfand, E.W., Leikauf, G.D., Lee, N.A., (1997). Interleukin-5 expression in the lung epithelium of transgenic mice leads to pulmonary changes pathognomonic of asthma. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 185(12), 2143-2156.

- Li, J., Jie, H.B., Lei, Y., Gildener-Leapman, N., Trivedi, S., Green, T., Kane, L.P., Ferris, R.L., (2015). PD-1/SHP-2 inhibits Tc1/Th1 phenotypic responses and activation of T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Research. 75(3), 508-518.

- Liu, C., (2013). Strategies for designing transgenic DNA constructs. Methods in molecular biology. 1027, 183-201.

- Liu, J., Yang, C., Lui, T., Deng, Z., Fang, W., Zhang, X., Li, J., Huang, Q., Liu, C., Wang, Y., Yang, D., Sukhova, G.K., Lindholt, J.S., Diederichsen, A., Rasmussen, L.M., Li, D., Newton, G., Luscinskas, F.W., Liu, L., Libby, P., Wang, J., Guo, J., Shi, G.P., (2020). Eosinophils improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Nature Communication. 11(1), 6396.

- Masterson, J.C., McNamee, E.N., Hosford, L., Capocelli, K.E., Ruybal, J., Fillon, S.A., Doyle, A.D., Eltzschig, H.K., Rustgi, A.K., Protheroe, C.A., Lee, J.J., Furuta G.T., (2014). Local hypersensitivity reaction in transgenic mice with squamous epithelial IL-5 overexpression provides a novel model of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 63(1), 43-53.

- Morimoto, M., Yamada, M., Arizono, N., Hayashi, T., (1998). Lactic dehydrogenase virus infection enhances parasite egg production and inhibits eosinophil and mast cell responses in mice infected with the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunology. 93, 540-545.

- McMillan, S.J., Richards, H.E., Crocker, P.R., (2014). Siglec-F-dependent negative regulation of allergen-induced eosinophilia depends critically on the experimental model. Immunology Letters. 160(1), 11-16.

- Nagase, H., Ueki, S.H., Fujieda, S.H., (2020). The roles of IL-5 and anti-IL-5 treatment in eosinophilic diseases: Asthma, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergology International. 69(2), 178-186.

- Nemeth, Z.H., Bogdanovski, D.A., Barratt-Stopper, P., Paglinco, S.R., Antonioli, L., Rolandelli, R.H., (2017). Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis show unique cytokine profiles. Cureus. 9(4), e1177.

- Nussbaum, J.C., Van Dyken, S.J., von Moltke, J., Cheng, L.E., Mohapatra, A., Molofsky, A.B., Thornton, E.E., Krummel, M.F., Chawla, A., Liang, H.E., Locksley, R.M., (2013). Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 502(7470), 245-248.

- Parry, R.V., Chemnitz, J.M., Frauwirth, K.A., Lanfranco, A.R., Braunstein, I., Kobayashi, S.V., Linsley, P.S., Thompson, C.B., Riley, J.L., (2005). CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25(21), 9543-9553.

- Rayapudi, M., Mavi, P., Zhu, X., Pandey, A.K., Pablo Abonia, J., Rothenberg, M.E., Mishra, A., (2010). Indoor insect allergens are potent inducers of experimental eosinophilic esophagitis in mice. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 88(2), 337-346.

- Todd, R., Donoff, B.R., Chiang, T., Chou, M.Y., Elovic, A., Gallagher, G.T., Wong, D.T., (1991). The eosinophil as a cellular source of transforming growth factor alpha in healing cutaneous wounds. American Journal of Pathology. 138(6), 1307-1313.0

- Wong, D.T., Donoff, R.B., Yang, J., Song, B.Z., Matossian, K., Nagura, N., Elovic, A., McBride, J., Gallagher, G., Todd, R., Chiang, T., Chou, L.S., Yung, C.M., Galli, S.J., Weller, P.F., (1993). Sequential expression of transforming growth factors α and β₁ by eosinophils during cutaneous wound healing in the hamster. American Journal of Pathology. 143(1), 130-142.

- Wynn, T.A., (2004). Fibrotic disease and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Nature Reviews Immunology. 4(8), 583-594.