Technical note

Necropsy observations of Arctic Common Eider (Somatria mollissima) and Thick-billed Murres (Uria lomvia) implanted with PTT-100 satellite transmitters

By Christian Sonne1, Anders Mosbech1,

Flemming Merkel1,4, Aage Kristian Olsen

Alstrup2*, Annette Flagstad3

1

Aarhus University, Faculty of Science and Technology, Department

of Ecoscience, Arctic Research Centre (ARC), Frederiksborgvej 399,

P.O. Box 358, DK-4000 Roskilde, Denmark (C. Sonne: cs@ecos.au.dk;

A. Mosbech: amo@ecos.au.dk; F. Merkel: frm@ecos.au.dk)

2

Department of Nuclear Medicine & PET, Department of Clinical

Medicine, Aarhus University, Palle Juul-Jensens Boulevard 165,

DK-8200 Aarhus N (aagealst@rm.dk)

3

Faculty of Health, University of Copenhagen, Department of Small

Animal Science, Dyrlægevej 16, DK-1870 Frederiksberg, Denmark

(af@sund.ku.dk)

4

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, Kivioq 2, PO Box 570,

GL-3900 Nuuk (flme@natur.gl)

Correspondence:

cs@ecos.au.dk (C. Sonne) and

aagealst@rm.dk (A.K.O. Alstrup).

Summary

We surgically implanted a 50 g PTT-100 (Platform Transmitter Terminal) in 21 Common Eiders (Somatria mollissima) and a 29 g PTT-100 in 10 Thick-billed Murres (Uria lomvia). After 2-4 months, one Common Eider implanted intracoelomically and two Thick-billed Murres implanted subcutaneously were harvested by local subsistence hunters and examined in the laboratory. External examination of the harvested birds did not reveal any morphological or pathological changes, while the surgical abdominal and cervical wounds seemed to have healed with granulation tissue in all three birds. Necropsy showed chronic inflammation and fatty necrosis in one of the murres, while the antenna Dacron cuffs were at skin level as originally attached for all three birds, with primary tissue healing and no signs of inflammation. In the eider, a few peritoneal adherences were found on the liver without additional signs of inflammation, while one murre had adherences and granulomatous tissue around the PTT with signs of severe inflammation and external rejection. These results indicate that birds can survive implantation of transmitters, even if inflammation develops around the implants. The study points to the importance of continuously refining the techniques for implanting devices in wild birds and performing necropsies on recovered birds.

Keywords:Implant; Post-mortem; PTT-100; Satellite telemetry; Seabirds; Surgery; Necropsy.

Introduction

Satellite telemetry has been applied to a broad variety of bird species to map migration routes, moulting, wintering and breeding sites around the world (Dougill et al. 2000; Huettmann and Diamond 2000; Merkel et al. 2007, Mosbech et al. 2006, 2007; Petersen et al. 1995, 1999, 2004; Washburn et al., 2022). These parameters are of interest when studying the influence of anthropogenic factors, including fossil energy sources, chemical and light pollution from cities and hunting, but also are relevant to investigations of zoonotic disease outbreaks such as bird-flu pandemics and climate-driven environmental changes (Wang et al., 2022). In the Arctic, Common Eiders (Somateria mollissima), King Eiders (Somateria spectabilis), Thick-billed Murres (Uria lomvia), Steller’s Eiders (Polysticta stelleri) and Spectacled Eiders (Somateria fischeri) have been satellite tracked to map spatial distribution, ecology, demographic patterns and population delineation information needed for planning oil exploration activities and management (Merkel et al. 2007; Meyers et al. 1998; Mosbech et al. 2006, 2007; Petersen et al. 1995, 2006). Employing Platform Transmitter Terminals (PTTs) for these investigations requires either external attachment – by use of glue or harnesses – or subcutaneous or intra-coelomic surgical implantation during anesthesia (Buck et al., 2021; Fast et al. 2011; Korschgen et al. 1996a, 1996b; Mulcahy, 2010; Sonne et al. 2011). Until now, only sparse information about the consequences of long-term implantation of PTTs has been available (Fast et al. 2011; Hupp et al. 2003, 2006; Latty et al. 2010; Meyers et al. 1998; Lameris et al., 2018; Geen et al., 2019) while reports on in situ location and pathology are absent in the international scientific literature. The purpose of the present paper is therefore to report post-mortem information on a Common Eider and two Thick-billed Murres harvested by local hunters in West Greenland several months following subcutaneous and intra-coelomic implantation with PTT-100 satellite transmitters as described by Sonne et al. (2011). Such necropsy information is important for scientists and veterinarians who want to conduct surgical field PTT implantations in wild birds - both to obtain reliable results from healthy birds, and to ensure good animal welfare in these wild experimental birds. Necropsies provide opportunities for refinement of implantations.

Materials and methods

Field sites and surgical implantation

The fieldwork and surgical study were approved by the Greenland veterinary authorities and by the Directorate of Environment and Nature (permission no. J.nr:28.40.50/2002). We implanted PTT-100 intra-coelomically in 21 Common Eiders and PTT-100 subcutaneously in 10 Thick-billed Murres in 2002 and 2005, respectively (Figure 1). The PTT-100 from Microwave Telemetry, Columbia, Maryland 21045 USA (https://www.microwavetelemetry.com/implantable_ptts) weighed either 50 g (eiders) or 29 g (murres) depending on the types of batteries supplied by the manufacturer.

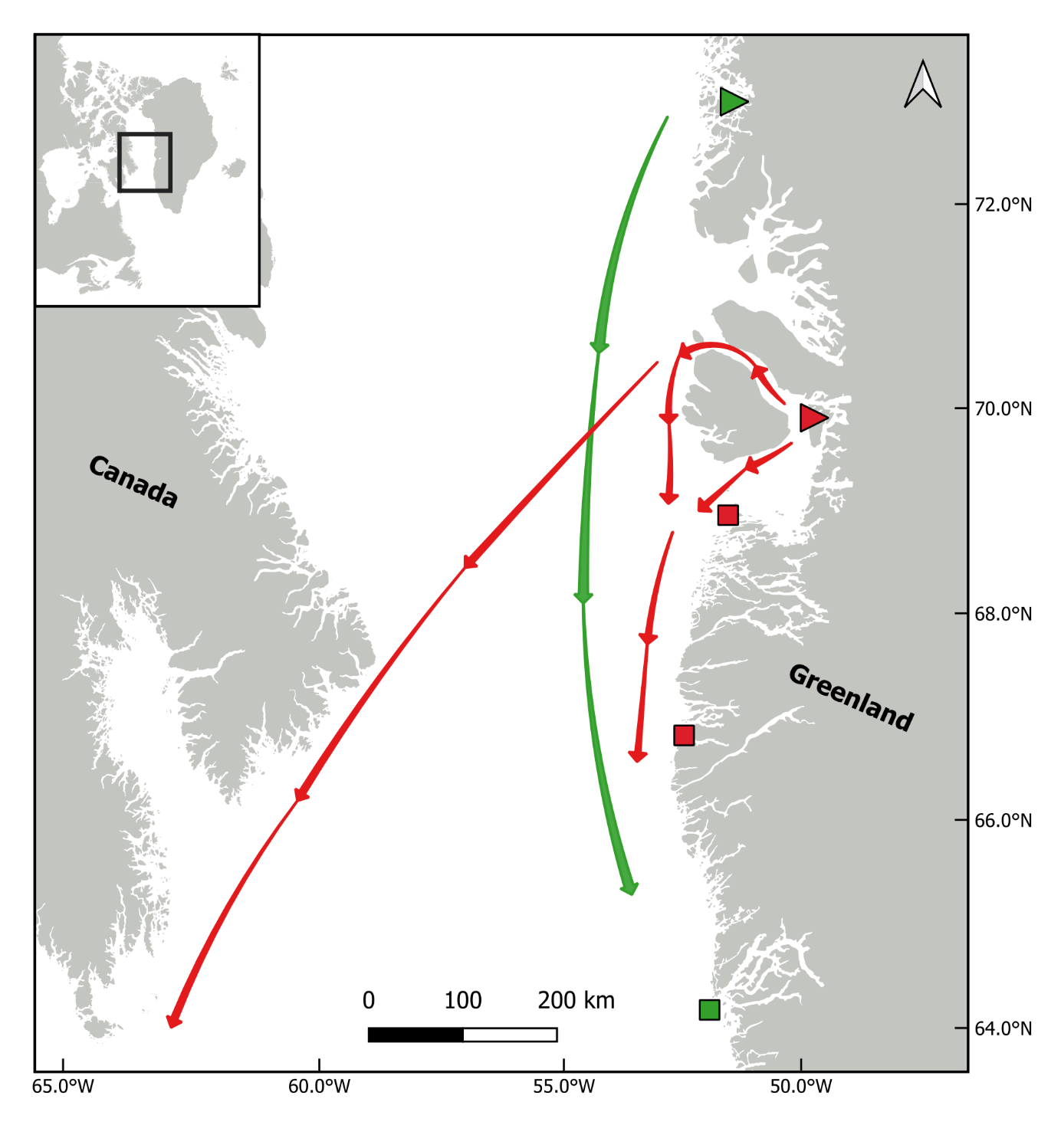

All 3 birds were captured in West Greenland as described by Mosbech et al. (2007) and Sonne et al. (2011). The two capture sites are shown in Figure 2 together with general movement patterns of the two species and the location of their harvest by local subsistence hunters. The eiders were caught in mist nets and nest traps at a colony in Upernavik June 2002 (Figure 3), while the murres were caught at Ritenbenk on their nest site in July 2005.

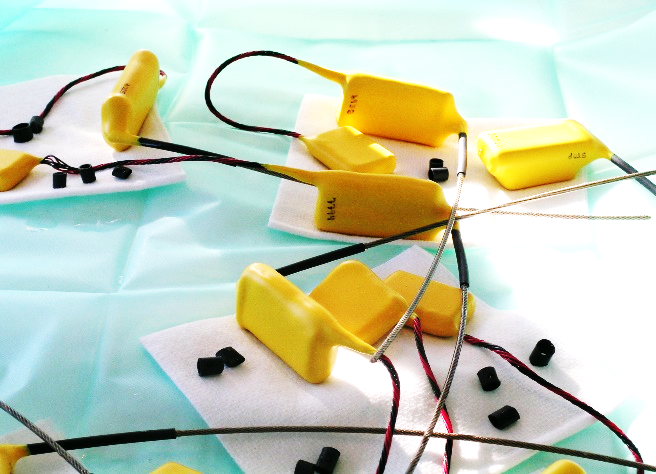

Both the pre-surgical preparations and surgical implantations followed Korschgen and coworkers (1996a, 1996b), but with some modifications as described by Sonne et al. (2011). PTT weights were less than 5% of body weights in both murres and eiders (range: 2.5-3.5%). Furthermore, as a refinement the PTTs were gently preheated to 35°C prior to implantation, as this would help to prevent hypothermia in the birds. The transmitters were pre-implantation disinfected in 70% medical ethanol/isopropyl alcohol for 12 hours and after implantation a sterile peritoneal Dacron cuff (DuPont® Dacron cuff, DuPont, Wilmington, North Carolina 28405, USA) was attached at the antenna base and secured with 5 mm sterile heat shrunk plastic coating. Corneal lubricant (80% Vaseline, 20% paraffin oil) was gently applied to the cornea to prevent dryness. Birds were anaesthetized through a closed-mask-system using Isoflurane (Isovet®, Merck & Co, Schering-Plough Animal health, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey 08889, USA) and medical oxygen (induction: 3% in 2000 ml O2 × min-1; maintenance: 1.5-4.5% in 2000 ml O2 × min-1) via a precision-vaporizer and a modified Bains’ coaxial system (Dameca Cyprane Limited Fluotec, Dameca a/s, DK-2610 Rødovre, Denmark). To reduce post-release heat loss, feather removal was avoided at the abdominal and cervical incision sites. Instead, the feathers were pushed aside by use of alcohol and subsequently taped. When needed, ice was applied to the webbed skin to reduce hyperventilation. The antenna exit site was prepared as dorso-cranially to the ischia bone as possible. Haemostatic forceps and a sharpened 4 mm urinary metal catheter were used to perforate the subcutis, muscle layer and peritoneum. The antenna was then pulled through the skin, and the cuff was secured tightly to the cutis and peritoneum with two single interrupted knots. Only the heat-shrunk plastic-coated antenna penetrated the skin. Murre surgeries were performed in a 12 m2 surgical theatre with temperature ranging 16.4 - 24.2°C, while eider surgeries were conducted in a boathouse with a temperature ranging 17.2 - 21.4°C (Table 1). The cloacal temperature (CT; °C) was continuously measured using an electronic thermometer with probe (OBH Nordica® Type 4850/51, OBH Nordica Denmark A/S, DK-2630 Taastrup, Denmark). Heat loss was compensated by placing an electric heat blanket (OBH Nordica® Type 4015, 50W, OBH Nordica Denmark A/S, DK-2630 Taastrup, Denmark; heat 1: low temperature at 30°C and heat 2: high temperature at 50°C) under the birds. In a few cases an aluminized rescue blanket (All Pro Rescue Blanket Co., Ltd., Qingdao 260035, China) was placed over the birds. In addition, a heat gun (Black & Decker, 2000W, Black & Decker Headquarters, Towson, Maryland 21286, USA) was used occasionally near the bird to warm up the surroundings. An electrocardiograph (ECG) (Schiller Cardiovit AT-4, Schiller AG, CH-6341 Baar, Switzerland) was employed to continuously monitor heart rate (HR; beats×min-1) which, together with extremity movements, corneal reflex and respiratory frequency (monitored but not logged), constituted the basis for adjustment of anaesthesia depth (Isoflurane %). Isotonic Ringers-acetate was used as vascular transmitter to obtain transduction of cardiac electric signal from skin to electrodes. Medical oxygen was administered until the bird had fully regained consciousness. The birds were held in a box fitted with absorbent pads until release 60-120 minutes post-surgery. All data were logged manually. Based on registration of PTT body core temperature, all released birds survived their first post-surgery month. As pain killer and antibiotics, we used meloxicam 0.5 mg/kg s.c. and enrofloxacin (Baytril) 10 mg/kg i.m. Information about the eider and two murres is shown in Table 1.

| Common Eider | Thick-billed Murre | Thick-billed Murre | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Upernavik, West Greenland | Ritenbenk, West Greenland | Ritenbenk, West Greenland |

| Ring | d779 | 413750 | 4137509 |

| PTT # | 307762 | 23168 | 7794 |

| Age, sex | Adult Female | Adult Female | Adult Female |

| PTT Type | I | S | S |

| Implanting Date | 21 June 2002 | 21 July 2005 | 22 July 2005 |

| Recapture date | 16 Oct 2002 | 10 Nov 2005 | 16 Sept 2005 |

| Implanting weight (g) | 1510 | 810 | 880 |

| Recapture weight (g) | 1887 | 769 | 925 |

| Wound #1 | Granulation tissue present. Primary tissue healing. No signs of inflammation | Granulation tissue present. Primary tissue healing. No signs of inflammation | Excessive scar (granulation) tissue present. Signs of chronic granulomatous inflammation and fatty necrosis. Secondary tissue healing. Open external pouch. |

| Wound #2 | Dacron cuff at skin level as originally placed. Primary tissue healing. No signs of inflammation | Dacron cuff at skin level as originally placed. Primary tissue healing. No signs of inflammation | Dacron cuff at skin level as originally placed. Primary tissue healing. No signs of inflammation. |

| PTT | Intra-coelomic as original implanted. A few peritoneal adherences to the liver were present. PTT in “pouch” of peritoneum. No signs of inflammation or antigenic reaction | Subcutaneous as original implanted. No adherences present. PTT in epithelial pouch. No signs of inflammation or antigenic reaction. Battery wire by suture in intervertebral ligament as originally placed. Battery in epithelial pouch as originally placed. | Subcutaneous as original implanted. Adherences and granulomatous tissue around PTT body. PTT in an open epithelial pouch. Signs of severe inflammation and external rejection of PTT due to inflammation and/or antigenic reaction. Battery wire by suture in intervertebral ligament as originally placed. Battery in pouch but in a phase of rejection. |

I: intra-coelomic. S: subcutaneous. Wound #1: abdominal/dorsa-cervical incision. Wound #2: antenna exit site.

Necropsy procedure

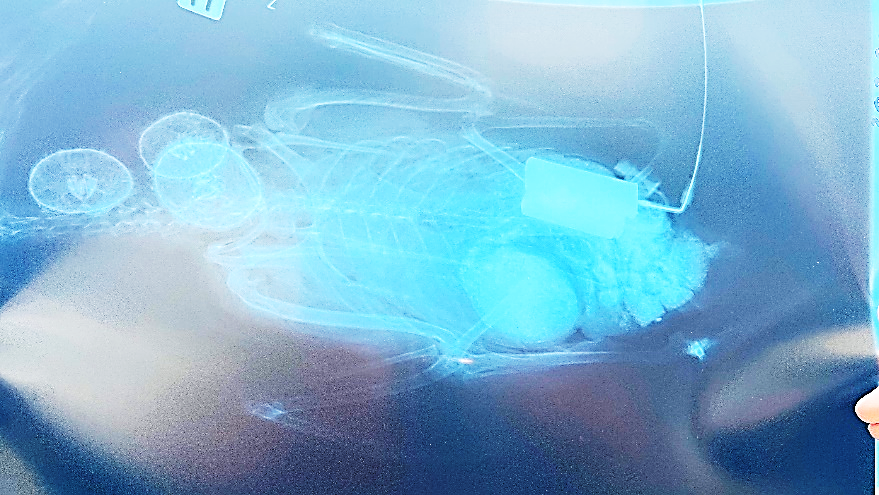

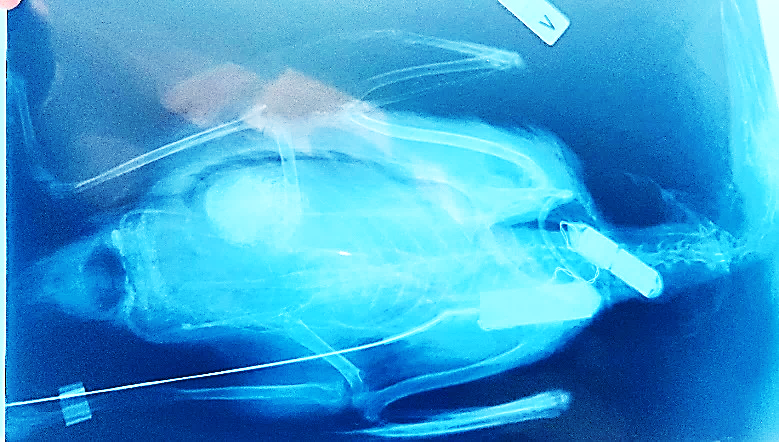

All three birds were harvested by local subsistence hunters and frozen when taken in the field and brought to the Department of Small Animal Science, Faculty of Health at University of Copenhagen, Denmark. First the birds were examined grossly (antenna and incision sites), and biometrics were measured. Then the birds were x-rayed to determine the in situ location of the PTT body and antenna, after which the birds were necropsied focusing on the wound healing procedures, the antenna exit site and encapsulation of the PTT body. Histopathology was conducted to diagnose gross pathology findings.

Results

The eider was an adult female implanted in June 2002 and harvested by local subsistence hunters in October 2002 south of Upernavik in West Greenland (Table 1). It had gained 377 grams (25%), and external examination of the bird did not reveal any morphological or pathological changes, while the surgical abdominal and cervical wounds seemed to have healed with granulation tissue. X-ray of the eider showed the in situ location of the PTT to have been maintained caudally in the coelomic cavity following implant and encapsulation (Figure 4A). Necropsy showed that there was granulation at the abdominal incision site with primary tissue healing and no signs of inflammation. At the pelvic percutaneous antenna exit site, the Dacron cuff was at skin level as originally placed with primary tissue healing and no signs of inflammation. The PTT was located intra-coelomically in a peritoneal pouch at the original implantation site with a few liver-peritoneal adherences, and with no signs of inflammation or antigenic reactions. The two murres were both adult females implanted in June 2005. One was harvested by subsistence hunters four months later in November 2005 at Itilleq south of Sisimiut in West Greenland and had only lost 41 grams (5%). According to the hunter the murre had shown normal behavior and was taken accidentally because the antenna was not visible prior to shooting. External examination of the bird did not reveal any morphological or pathological changes, while the surgical cervical wounds seemed to have healed with granulation tissue. X-ray of the murre showed the in situ placement maintained for both the transmitter body and battery at the cervical incision along the scapula and cervical vertebrae (Figure 4B). Necropsy showed that the cervical incision had granulation tissue present with primary tissue healing and no signs of inflammation. The PTT was positioned as originally implanted and there were no adherences; the PTT was located in an epithelial pouch. At the percutaneous antenna exit site, the Dacron cuff was at skin level as originally placed with primary tissue healing and no signs of inflammation. Battery wire was located by the suture in the intervertebral ligament as originally placed and the battery was in an epithelial pouch as originally placed.

The second murre was harvested by local subsistence hunters in September 2005, two months after implantation, near Aasiaat in West Greenland. It had gained 45 grams in weight (5%). Necropsy showed that around the cervical incision site,excessive granulation tissue was present with signs of chronic granulomatous inflammation and fatty necrosis, and with the PTT in an open external epithelial pouch. The battery wire was located by the suture of the intervertebral ligament as originally placed with no signs of inflammation. However, the battery was in a pouch but in a phase of rejection being located more proximally than the original cervical placement. At the percutaneous antenna exit site, the Dacron cuff was at skin level as originally placed and included primary tissue healing.

Discussion

These kinds of field studies are associated with the significant challenge that experimental animals typically cannot be observed after they are released following tagging, surgery or other experimental procedures. It is therefore important that all the procedures are carried out so that animal welfare is good from the beginning, as it is not normally possible later to medically treat or euthanize the animals. Here, necropsies of the animals provide valuable knowledge that can optimize procedures. Even a small number of necropsied animals can, as here, provide knowledge of significant importance. The study emphasizes the importance of refining experimental procedures on wild birds. Surgery should be performed as aseptically as possible under field conditions. The use of antibiotics together with painkillers can be considered, but it should be remembered that treatment cannot be resumed after the bird has been set free. Careful planning of procedures that allow for refinement is therefore important, albeit difficult during field trials. The rule of thumb is to keep the transmitter weight at a maximum of 5% of body weight to avoid changes in body draft and weight balance (Casper 2009, Barron et al. 2010). The PTT-100 transmitters with percutaneous antennae used in the present study were quite large and the surgical implantation probably had more impact compared to smaller ones. The large size can lead to limping and limited feeding, diving, flight and mobility (Latty et al. 2010). Guillemette et al. (2002) implanted Common Eiders with 16-gram data loggers and no effects were found on hatching success, laying dates and clutch size compared to control females. Fast et al. (2011) reported on female Common Eiders implanted with a PTT-100 and showed that, compared to controls, no differences in time allocated to basic behaviors. Surprisingly, the implanted birds were not more likely to pick or preen their surgical sites. The implanted females showed a lower survival rate the year after implantation compared to controls (Fast et al. 2011). The following years no difference could be found in survival. This shows that PTT implantation in Common Eiders leads to a decline in survival in the first years and some short-term behavior changes. Modern PTT implants weigh around 29-50 grams (https://www.microwavetelemetry.com/implantable_ptts), but if they can be made smaller in the future, it will undoubtedly present the potential for refinement Any temperature change and handling-induced stress require increased foraging, resting and preening to increase immune competence, maintain homeostasis, and counteract altered dive performance (Davis and Bissonnette 1999; Latty et al. 2008a, 2008b; Olsen and Perry 2008a, 2008b). Such adverse effects should be avoided if possible. Surgical stress may prolong recovery time and subsequently reduce both reproductive success and survival (Davis and Bissonnette 1999; Latty et al. 2008a, 2008b; Olsen and Perry 2008a, 2008b). The number of necropsied birds is a limitation in this study. The study cannot therefore give a true picture of how often complications arise after implantation of such devices in wild birds. A larger number of necropsies is therefore needed in future studies.

Conclusions

We have necropsied three birds with GPS transmitters, one eider and two murres. While no signs of inflammation were detected in two birds, one murre was characterized by chronic inflammation. The study points to the importance of refining surgical interventions on wild birds and evaluating the techniques by necropsying birds successfully collected after death occurred.

Acknowledgements

The Bureau of Minerals and Petroleum in Nuuk is acknowledged for financial support, and Allan Juhl Kristensen and Rune K. Ritz are acknowledged for collecting Thick-billed Murres on their nest sites and Kasper Lambert Johansen is acknowledged for database management and for providing input to Figure 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Barron, D. G., J. D. Brawn, and P. J. Weatherhead. 2010. Meta-analysis of transmitter effects on avian behaviour and ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 1:180-187.

- Buck, E.J., Sullivan, J.D., Kent, C.M., Mullinax, J.M., Prosser, D.J. (2021) A comparison of methods for the long-term harness-based attachment of radio-transmitters to juvenile Japanese quail (Coturnix japocica). Animal Biolelemetry 9(32):1-16.

- Casper, R. M. 2009. Guidelines for the instrumentation of wild birds and mammals. Animal Behaviour 78:1477–1483.

- Dougill, S.J., Johnson, L., Banko, P.C., Goltz, D.M., Wiley, M.R., Semones, J.D. (2000). Consequences of antenna design in telemetry studies of small passerines. Journal of Field Ornithology 71:385-388.

- Fast PLF, Fast M, Mosbech A, Sonne C, Gilchrist HG, Descamps S (2011): Effects of implanted satellite transmitter on behaviour and survival of female common eiders. Journal of Wildlife Management 75:1553–1557.

- Geen, G.R., Robinson, R.A., Baillie, S.R. (2019) Effects of tracking devices on individual birds – a review of the evidence. Journal of Avian Biology 50(2):1-13.

- Guillemette, M., A. J. Woakes, A. Flagstad, and P. J. Butler. 2002. Effects of data-loggers implanted for a full year in female Common Eiders. Condor 104:448-452.

- Huettmann, F., Diamond, A.W. (2000). Seabird migration in the Canadian northwest Atlantic Ocean: moulting locations and movement patterns of immature birds. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78:624-647.

- Hupp, J.W., Ruhl, G.A., Pearce, J.M., Mulcahy, D.M., Tomeo, M.A. (2003). Effects of implanted radio transmitters with percutaneous antennas on the behavior of Canada geese. Journal of Field Ornithology 4:250-256.

- Hupp, J.W., Pearce, J.M., Mulcahy, D.M., Miller, D.A. (2006). Effects of abdominally implanted radiotransmitters with percutaneous antennas on migration, reproduction, and survival of Canada geese. Journal of Wildlife Management 70:812-822.

- Korschgen, C.E., Kenow, K.P., Gendron-Fitzpatrick, A., Green, W.L., Dein, F.J. (1996a). Implanting intra-abdominal radiotransmitters with external whip antennas in ducks. Journal of Wildlife Management 60:132–137.

- Korschgen, C.E., Kenow, K.P., Green, W.L., Samuel, M.D., Sileo, L. (1996b). Technique for implanting radio transmitters subcutaneously in day-old ducklings. Journal of Field Ornithology 67:392–397.

- Lameris, T.K., Müskens, G.J.D.M., Kölzsch, A., Dokter, A.M., Jeugd, H.P.V.D., Nolet, B.A. (2018) Effects of harness-attached tracking devices on survival, migration, and reproduction in three species of migratory waterfowl. Animal Biotelemetry 6(7):1-8.

- Latty, C.J., Hollmén, T.E., Petersen, M.R., Powell, A.N., Andrews, R.D. (2008A). Biochemical and clinical responses of common eiders to implanted satellite transmitters. The Third North American Sea Duck Conference, Québec City, Canada, 10–14 November 2008.

- Latty, C.J., Hollmén, T.E., Petersen, M.R., Powell, A.N., Andrews, R.D. (2008B). Dive performance of common eiders implanted with satellite transmitters. The Third North American Sea Duck Conference, Québec City, Canada, 10–14 November 2008.

- Latty, C.J., Hollmén, T.E., Petersen, M.R., Powell, A.N., Andrews, R.D. (2010). Abdominally implanted transmitters with percutaneous antennas affect the dive performance of common eiders. Condor 112:314-322.

- Merkel, F.R., Mosbech, A., Sonne, C., Flagstad, A., Falk, K., Jamieson, S.E. (2007). Local movements, home ranges and body condition of Common Eiders Somateria mollissima wintering in Greenland. Ardea 94:639-650.

- Meyers, P.M., Hatch, S.A., Mulcahy, D.M. (1998). Effect of implanted satellite transmitters on the nesting behavior of murres. Condor 100:172-174.

- Mosbech A., Gilchrist G., Merkel F., Sonne C., Flagstad A. & Nyegaard H. 2006. Year-round movements of Northern Common Eiders Somateria mollissima borealis breeding in Arctic Canada and West Greenland followed by satellite telemetry. Ardea 94(3): 651–665.

- Mosbech, A., Danø, R.S., Merkel, F.R., Sonne, C., Gilchrist, H.G. (2007). Use of satellite telemetry to locate key habitats for King Eiders (Somateria spectabilis) in western Greenland. In: Boere, G.C., Galbraith, C.A. & Stroud, D.A. (eds): Waterbirds around the world. A global overview of the conservation, management and research of the world's waterbird flyways. Edinburgh Stationery Office 769-776.

- Mulcahy, D.M. (2010) Are subcutaneous transmitters better than intracoelomic? The relevance of reporting methodology to interpreting results. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(3):884-889.

- Olsen, G.H., Perry, M.C. (2008A). Behavioural and physiological observations of white-winged scoters with surgically implanted transmitters. The Third North American Sea Duck Conference, Québec City, Canada, 10–14 November 2008.

- Olsen, G.H., Perry, M.C. (2008B). Surgical implantation of satellite transmitters: techniques for improving results based on captive diving duck studies. The Third North American Sea Duck Conference, Québec City, Canada, 10–14 November 2008.

- Petersen, M.R., Douglas, D.C. (1995). Use of implanted satellite transmitters to locate Spectacled Eiders at-sea. The Condor 97:276-278.

- Petersen, M.R., Larned, W.W., Douglas, D.C. (1999). At-sea distribution of Spectacled Eiders: A 120-year-old mystery resolved. Auk 116(4):1009-1020.

- Petersen, M.R., Douglas, D.C. (2004). Winter ecology of Spectacled Eiders: Environmental characteristics and population change. The Condor 106:79-94.

- Petersen, M.R., Bustnes, J.O., Systad, G.H. (2006). Breeding and moulting locations and migration patterns of the Atlantic population of Steller’s eiders Polysticta stelleri as determined from satellite telemetry. Journal of Avian Biology 37:58-68.

- Sonne, C., Andersen, S., Mosbech, A., Flagstad, A., Merkel, F.R. (2011). Implantation of PTT-100 satellite-transmitters in Greenland Sea birds: field monitoring of surgical parameters and their implications. Veterinary Medicine International 423010.

- Washburn, B.E., Maher, D., Beckerman, S.F., Majumdar, S., Pullins, C.K., Guerrant, T.L. (2022) Monitoring raptor movements with satellite telemetry and avian radar systems: an evaluation for synchronicity. Remote Sensation 14(11):2658.

- Wang, C.X., Xiu, L.-S., Hu, Q.-Q., Lee, T.-C., Liu, J., Shi, L., Zhou, X.-N., Guo, X.-K., Hou, L., Yin, K. (2023) Advancing early warning and surveillance for zoonotic diseases under climate change: interdisciplinary systematic perspectives. Advances in Climate Change Research 14(6):814-826.